Removal History of the Delaware Tribe

From “Removal and the Cherokee-Delaware Agreement,” in Delaware Tribe in a Cherokee Nation, by Brice Obermeyer. University of Nebraska Press, 2009. Pp. 37-48, 52-58.

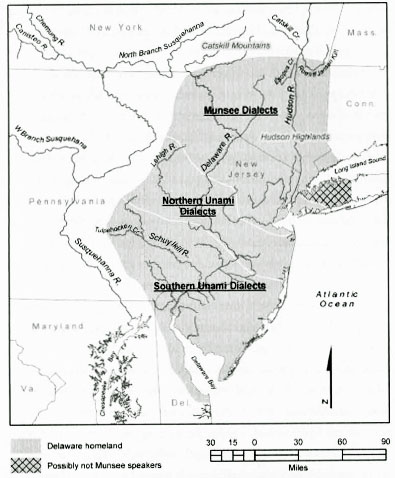

The Delaware Tribe is one of many contemporary tribes that descend from the Unami- and Munsee-speaking peoples of the Delaware and Hudson River valleys. Munsee and Unami are two closely related Algonquian dialects that were easily distinguishable from the languages of the other coastal Algonquian groups (Goddard 1978:213). The Unami and Munsee aboriginal homeland is situated within what are today the states of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, and Delaware. Munsee was the Algonquian dialect spoken in the villages along the upper Delaware and lower Hudson rivers while the Unami dialect that contained southern and northern variants existed along the lower Delaware river. The material culture differences between the Proto-Munsee and Proto-Unami villagers of the Hudson and Delaware valleys can be recognized as early AD 10,000, suggesting an antiquity in the cultural barriers between the Unami and Munsee speakers (Kraft 1984:7-8).2

The name collectively attributed to the descendants of such Unami and Munsee people is Delaware, yet the word Delaware is not of indigenous origin, nor did the Munsee and Unami speakers conceive of themselves as a united political organization until the eighteenth century. The term Delaware actually derives from the title given to Sir Thomas West or Lord de la Warr III, who was appointed the English governor of Virginia in 1610. When Captain Samuel Argall first explored what would later be named the Delaware Bay and River, he chose the name Delaware to honor the newly appointed Virginia governor (Kraft 1984:1). European colonists later applied the term in varied dialectical forms to reference the Unami-speaking groups of the middle Delaware River valley, and by the late eighteenth century the term had been extended to include all of the Unami-and Munsee-speaking peoples living in or removed from the Delaware and Hudson River valleys (Goddard 1978:213, 235; Weslager 1972:31). The southern Unami self-designation is Lenape, which roughly translates as “People” and was the term used by the inhabitants of the lower Delaware River. Most Delaware in eastern Oklahoma descend from such Unami speakers, with only a minority who count Munsee descent as well Today, the southern Unami dialect is the language learned and used by the Delaware in eastern Oklahoma, and Delaware is the tribal name used by most tribal members, with Lenape as an often used synonym.

1. DELAWARE HOMELAND: The seventeenth-century Delaware territory and distribution of Munsee and Unami dialects. Adapted from lves Goddard, “Delaware,” in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast, ed. Bruce Trigger and William Sturtevant (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), p. 214, figure 1. Map by Rebecca Dobbs. 3 By the time that the English wrested possession of the region from the Dutch in 1664, the Unami and Munsee had already been pressured to leave portions of their original homelands (Weslager 1972:98-136; Goddard 1978:220). The British subsequently established new settlements or renamed existing Dutch villages, and the growing number of English immigrants arriving in the late seventeenth century put further pressure on the Unami and Munsee to cede more land (Weslager 1972:137-152).

Two centuries of European encroachment ultimately led to the removal of the Unami and Munsee speakers from the Delaware and Hudson River valleys to the frontier of English occupation. The allied Six Nations and the English combined forces in the eighteenth century and relied upon misleading treaty agreements and the threat of military force to ultimately push the Unami and Munsee people to abandon their remaining homelands and move west. By the mid-eighteenth century, the majority of Munsee and Unami speakers had joined several villages along the Susquehanna, Allegheny, and Ohio rivers and were by then referred to collectively as the Delaware (Goddard 1978:213-216). Other displaced coastal and interior Algonquians such as the Shawnee, Conoy, and Nanticoke often joined the Delaware villages on the frontier (Weslager 1972:173-193; Goddard 1978:221-222). The refugees were then settled within territory claimed by the Iroquois, and the newly arrived residents were obliged to live as protectorates of the Six Nations (Weslager 1972:180, 196-208).4 Since authority among the Delaware villagers rested in a group of sachems, British officials and Iroquois diplomats were often frustrated in their attempts to deal with the displaced peoples and broker land deals with the refugee villagers. The Iroquois and the English subsequently pressured the Delaware groups to name a king who could represent the different villages and with whom the colonial government could engage treaty negotiations (Weslager 1978:14-15). Though paramount leaders were named for the displaced villagers, it is clear that such designated Delaware chiefs of the eighteenth century held a somewhat tenuous authority over the entirety of their people (A. Wallace 1970; Weslager 1972:209; Goddard 1978:223).

As the independent Munsee and Unami bands coalesced in frontier villages, the political life of such groups followed a pattern by which the independent village sachems centralized under a clan-based governing body. The Delaware political system that emerged in the mid-eighteenth century consisted of three clan chiefs who represented three matrilineal clans, the Wolf, Turkey, and Turtle clans. One clan chief acted as the first among equals and served as the Delaware spokesman (Goddard 1978:222; Weslager 1972:250). Each clan chief was also attended by councilors and war captains of the same clan. War captains were responsible for declaring war and protecting the people, while only the clan chiefs could declare peace. The councilors served as personal advisers for each clan chief (Zeisberger 1910:98).5

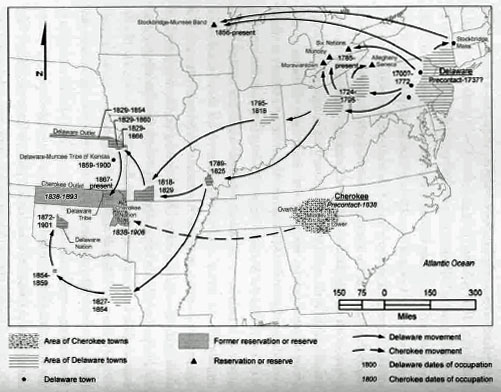

The tumultuous years surrounding the American Revolution led to a Delaware diaspora that would further define the nucleus of the Delaware Tribe and create the boundaries between the many Delaware-descended groups that exist today. By the eve of the American Revolution, most Delaware groups were living along the Ohio and Allegheny rivers. The pro-British Delaware groups were living in what is today the northwestern portion of Ohio, and pro-American Delaware groups were settled near the frontier city of Pittsburgh (Goddard 1978:222-223). Despite the mixed alliance, the Delaware were largely treated as defeated British allies at the close of the war. Following the American Revolution, different Delaware groups migrated north and west to Canada and Spanish Territory in order to escape American retaliation while others stayed within the Ohio Territory.6

Three groups relocated to Canada following the American Revolution. The first group consisted of a few Northern Unami bands who had not followed the main body to the frontier and who joined the Iroquois on the Six Nations Reserve along the Grand River in what is today Ontario (Goddard 1978:222). The Delaware living on the Six Nations Reserve have maintained an identity separate from the Iroquois but are today considered members of the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory. a recognized First Nation of Canada. A second group of Canadian Delaware were originally Christian converts who followed the Moravian missionary David Zeisberger north to Canada after the American Revolution and, in 1792, established what would later become known as Moraviantown along the Thames River in Kent County, Ontario. The Moravian migration followed the Gnadenhutten Massacre of 1782 when the American militia slaughtered ninety peaceful Moravian Delaware living in the mission village of Gnadenhutten, Ohio (Goddard 1978:223). The third group relocating to Canada was a collection of pro-British Munsee bands who lived in northwestern Ohio during the American Revolution and who elected to settle at Munceytown along the Thames River in Canada prior to the arrival of the Moravian Delaware. Both the Moravian Delaware (Delaware of the Thames) and the Munceytown Delaware (Muncee-Delaware) are recognized today as First Nations in Canada.

Other Delaware groups decided to move further west to Spanish territory or remain within the boundaries of the new American state. The earliest movement consisted of both Unami and Munsee speakers who elected to move further west in 1789 to a settlement near what is today Cape Girardeau, Missouri, at the invitation of the Spanish after the American Revolution. Following a series of subsequent removals, the Cape Girardeau Delaware would later settle in Texas and eventually end up on a reservation with the Caddo and Wichita in what is today western Oklahoma. The western Oklahoma Delaware are federally recognized today as the Delaware Nation and are headquartered in Anadarko, Oklahoma (Goddard 1978:223; Hale 1987). A second migration consisted of a few small groups of Christian Munsee and Unami converts who managed to remain behind along the Hudson and Delaware River valleys following the American Revolution. The converts were eventually relocated with other Munsee and Mahicans living at Stockbridge, Massachusetts, to a reservation in Wisconsin. The descendants of such Munsee, Unami, and Mahicans are a federally recognized tribe today known as the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mahican Indians (Goddard 1978:222). A third group of predominately Munsee speakers settled with the Senecas along the Allegheny River in 1791, where they eventually merged with the Seneca by the twentieth century (Goddard 1978:223). Today, the descendants of such assimilated Munsee are members of the Seneca Nation of Indians who are located on the Allegany Indian Reservation in southwestern New York and are also a federally recognized tribe. Munsee and Unami descendant groups are thus scattered widely throughout North America, and most are recognized as members of acknowledged Indian Tribes in the United States or as First Nations in Canada.7

The Delaware Tribe of today is composed of the descendants of the so-called main body of Delaware who elected not to relocate north or west but remained in Ohio following the American Revolution. There the Delaware Tribe became a powerful frontier force that participated in the intertribal resistance to the new American government during the late eighteenth century (Weslager 1972:317-322; Goddard 1978:223). Delaware military action against the United States ultimately ended when the Americans defeated the intertribal confederacy that included Delaware, Shawnee, and other woodland Indian forces at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1795. Following the defeat, the Delaware and others surrendered to the United States and signed the Treaty of Greenville after which they would never again take up arms against the Americans (Weslager 1972:322). The main body then joined other Delaware who had earlier settled, at the invitation of the Miami, along the White River in what is now Indiana (Weslager 1972:333; Goddard 1978:224).

It was along the White River that leadership became further centralized and a new, religiously conservative Delaware government emerged. A revitalization movement took place among the Delaware settled along the White River that institutionalized a renewed sense of Delaware identity in opposition to Christianity. The new leadership blamed the Christian influence for the Delaware’s inability to defeat the Americans. Missionaries were banned from Delaware lands, and the clan chiefs selected to govern were those men who were also ceremonial leaders and visionaries within the revitalized Big House Ceremony. Clan membership still determined the appropriate leaders, but now participation in the Big House Ceremony further strengthened one’s ability to gain support within the clan (A. Wallace 1956:16; J. Miller 1994:246-247). During the settlement along the White River the Delaware began to recognize the ascendancy of a principal chief among the clan chiefs as the Delaware elevated Chief Anderson’s position from a first among equals to the position of principal or head chief (Cranor 1991:5).

2. DELAWARE AND CHEROKEE REMOVAL: The chronology and routes of the separate Delaware and Cherokee removals to Indian Territory. Official dates are given, but occupation may have preceded and followed these dates. Many additional Delaware settlements and movements existed, and the divisions between the seven identified Delaware groups cannot be traced to the eighteenth century, as smaller groups consistently moved back and forth between what appear as bounded groups into the twentieth century. Adapted from Ives Goddard, “Delaware,” in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast, ed. Bruce Trigger and William Sturtevant (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution1 1978), p. 214, figure 11 and p. 222, figure 5, and from Raymond D. Fogelson, “Cherokee in the East,” in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 14: Southeast, ed. Raymond O. Fogelson and William Sturtevant (Washington DC: Smithsonian institution, 2004), p. 338, figure 1. Map by Rebecca Dobbs. 8 Beginning in 1829 and ending by 1831, the Delaware Tribe moved again, this time to the junction of the Kansas and Missouri rivers in present-day northeastern Kansas (Weslager 1972:357-372; Goddard 1978:224). The Delaware reestablished towns along the Kansas River and soon prospered from the emerging industry surrounding the migration of American settlers to the West for which the Delaware served as traders, ferry operators, military scouts, and guides (Farley 1955).

The anti-Christian sentiment of the early nineteenth century lapsed on the Kansas reservation, and Christian missionaries were allowed to return.9 The missionaries soon set up schools and churches on the Delaware reservation, and many influential Delaware were either educated or converted by the Baptist, Methodist, or Moravian missions (Farley 1955; Weslager 1972:373-387). By the 1860s some of the clan leaders constituting the Delaware Council were also Christian converts (Weslager 1972:384-388). While the influence of Christianity on the Delaware Tribal Council was apparent, leadership positions continued to be achieved through matrilineal clan ascendancy until the mid-1860s (Weslager 1972:388).10 Thus, by the time of the Delaware’s last removal to the Cherokee Nation, Delaware society was a religiously diverse population living in agrarian frontier villages with a clan-based political organization that maintained a strong alliance with the United States.11

ARTICLES OF AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE CHEROKEE NATION AND THE DELAWARES, APRIL 8, 1867

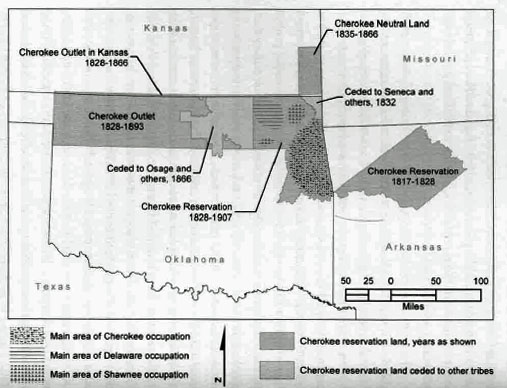

Following the Civil War, white encroachment and railroad speculation increased, and the Delaware were pressured to cede their lands in Kansas and relocate to Indian Territory (Weslager 1972:399-429i Goddard 1978:224). In 1866 the U.S. government signed its final treaty with the Delaware Tribe, ending one of the longest ongoing treaty relationships between the federal government and an Indian tribe.13 Under the Treaty with the Delaware, 1866, or 1866 Delaware Treaty, the Delaware Council agreed to give up their reservation in Kansas and move to a region of their choosing on lands ceded to the federal government by the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, or Seminole, “or which may be ceded by the Cherokees in the Indian Country” (Carrigan and Chambers 1994:A4). The lands to be chosen by the Delaware were to be selected in as compact a form as possible and include an area equal to 160 acres for each man, woman, and child who chose to relocate. Given that a total of 985 Delaware eventually removed to the Cherokee Nation, the land selected for removal would have had to be equivalent to 157,600 acres or roughly 250 square miles. A handful of Delaware elected to remain in Kansas, and according to the treaty such individuals could do so only if they dissolved their membership in the Delaware Tribe. The Delaware who stayed in Kansas subsequently became American citizens, and their land was held in severalty by the secretary of the interior (Weslager 1972:423). Clinton A. Weslager (1972:516-517) lists the nineteen Delaware families who chose to stay in Kansas, but the Delaware Tribe did reinstate a few families who later decided to join their relatives in Indian Territory following removal.14 Today, the Delaware-Muncee Tribe is headquartered in Ottawa, Kansas, and is recognized by the state as the descendants of those Delaware who elected not to remove to the Cherokee Nation.

It was thus made clear to the Delaware by the 1866 Delaware Treaty that removal was the only route available to ensure the continuation of the Delaware Tribe. Cognizant of the mounting pressure for removal and the desire to preserve the Delaware Tribe, Delaware clan leaders began exploring and scouting different locations for a new reservation in Indian Territory as stipulated by the 1866 treaty. It was determined that the Delaware desired the unoccupied lands in what is now northeastern Oklahoma immediately east of the ninety-sixth degree of longitude (Weslager 1972:423-424). Since the land belonged to the Cherokee Nation at the time, the Delaware decided to purchase a 10-by-30-mile tract of land from the Cherokee Nation that was situated along the upper Caney River valley. In an 1866 letter from principal Delaware chief John Conner (maternal grandson of Delaware chief William Anderson) to Cherokee chief William P. Ross, Conner explained that the Delaware had selected a tract east of the ninety-sixth parallel because of the perceived productivity of the land and in order to preserve the Delaware tribal organization (Conner 1866). Consistent with the 1866 treaty, the Delaware had selected a compact area of land that contained 300 square miles or 192,000 acres, only slightly larger than the required 250 square miles or 157,600 acres.

Chief Conner’s request for the right to purchase a 10-by-30-mile tract of land from the Cherokee Nation was also consistent with the Treaty with the Cherokee, 1866, a treaty being signed at the same time between the Cherokee Nation and the federal government. In this treaty the Cherokee Nation agreed to sell their lands west of the ninety-sixth degree of longitude for the resettlement of friendly Indians. The relocated friendly Indians were to pay the Cherokee Nation for the land and afterward would hold the land as their own separate reservation. From the land cession, the federal government then had the space to remove what were primarily tribes from the newly organized states of Kansas and Nebraska to reservations in Indian Territory.15 Land east of the ninety-sixth degree of longitude, however, remained in the possession of the Cherokee Nation but was made available for the resettlement of what the federal government referred to as “civilized Indians.”

The 1866 Cherokee Treaty spelled out two options that were available for civilized Indians wishing to settle within the boundaries of the Cherokee Nation. The first option, also known as the incorporation option, was for the Indian tribe being removed to abandon their tribal organization and become Cherokee citizens. Tribes who wished to adopt Cherokee citizenship had only to pay the Cherokee Nation a sum of money for the right to citizenship, and they would ever after be treated as native citizens. On the other hand the second option, also known as the preservation option, allowed for the Indians being removed to preserve their tribal organization in ways that were not inconsistent with the constitution and laws of the Cherokee Nation. Tribes who selected the preservation option in order to continue their tribal structure were required to pay two separate payments to the Cherokee Nation. The first payment was for citizenship that granted the relocated tribe the right to hold all rights as native Cherokee citizens. The second payment was for a parcel of land equal to 160 acres per man, woman, and child that would be set aside for the occupancy of the relocating tribe. It would appear then that the letter from Chief John Conner was informing the Cherokee Nation of the Delaware Tribe’s intent to pursue the preservation option as stipulated by both the 1866 Delaware Treaty and the 1866 Cherokee Treaty with the United States. The Delaware thus agreed to removal so they would not become American citizens and chose the preservation option in the 1866 Cherokee Treaty in order to preserve their tribal government and not merge with the Cherokee Nation upon removal. The purchase of land equivalent to 160 acres per removed Delaware was pursued in order to sustain an independent Delaware Tribe that was now going to occupy lands in the Cherokee Nation.

(Note: Endnotes are those in the book; endnotes 2-11 and 13-15 are included in this secction.) 2. For a general overview on the archaeology of this region I refer the reader to the major works of Herbert Kraft (1974, 1977, 1984, 1986). 3. For more information on the history of Dutch colonialism in New Netherland see van Laer (1924), Brasser (1974), Weslager (1972, 1986), and Kraft (1996). 4. Although officially loyal to the English through the Iroquois, the Delaware never relinquished the right to make their own political decisions (Weslager 1972:196-218; Goddard 1978:223). During the French and Indian War, for example, Delaware leaders pledged loyalty to both the French and the English simultaneously (Weslager 1972:221-260). In the American Revolution, the majority of Delaware leaders initially aided the Americans, but later switched to the British as more and more Delaware were forced westward during the course of the war (Weslager 1972:294-315). 5. That indigenous political systems of Woodland peoples have shifted over time is well documented. For the impact of the fur trade on the indigenous political systems of the Northeast see Cayton and Teute (1998), Jennings (1975), and White (1991). The historical literature also describes the impact that forced relocations and the so-called king-making policies of the British had on the Delaware clan structure and the centralization of Delaware governance (Thurman 1973; Wallace 1947, 1956, 1970; Schutt 2007). The reader is directed to Goddard (1978:225) for an overview of Delaware clan-based political organization. While the antiquity of the Delaware clan system of governance is unknown, such a governing system is associated with village leadership, which indicates that it probably existed prior to the arrival of Europeans. Jay Miller (1989:2-3) indicates that the Delaware aboriginal political system was founded on a symbolic connection between a chief who was the paramount leader of the clan that was associated with its own town. The ascendancy of clan identity as the primary system of governance over town affiliation in the eighteenth century was probably due to the refugee experience during that era. Despite such significant pressures on the Delaware to centralize authority, appointed Delaware chiefs frequently faced opposition groups within the tribe who gave voice to their dissent by recognizing their own leadership and alliances with enemy forces (Weslager 1972:296). 6. The historical migrations of the divergent Delaware groups are generalized here. For a more rigorous review of the multiple Delaware migrations, see Goddard (1978) and Weslager (1972, 1978). 7. There were individuals who likely veiled their indigenous descent throughout the American Revolution in order to remain in their homelands. 8. Research on the short period of Delaware occupation in southwest Missouri has been nonexistent, yet this is an important time period for understanding the cultural changes that took place in Delaware society as they adapted to and became familiar with the peoples and ecology of the Prairie Plains region. See Gina S. Powell and Neal H. Lopinot’s (2003) multiyear archaeological work on the Delaware occupation in Missouri as well as Melissa Ann Eaton’s (n.d.) unpublished dissertation for the most comprehensive work on the Delaware in Missouri. 9. Following the nativistic movement in 1806, led by Chief Anderson and described in detail by Jay Miller (1994), the Delaware banned Christian missionaries from access to the tribe. Later, when Issac McCoy traveled to the Delaware settlements on the White River, some chiefs promised him that he could return after the tribe was relocated west of the Mississippi. McCoy kept in contact with the Delaware during their sojourn in southwest Missouri, and when the Delaware finally relocated to their reserve in what would later be northeast Kansas, he was the official surveyor of the Delaware reserve. In 1836 Rev. Ira Blanchard established a Baptist mission school near Edwardsville. After the mission was destroyed by a flood, Rev. John Pratt rebuilt it on higher ground, and prominent Delaware leaders such as Charles Joumeycake and John and James Conner were active in this church. Pratt later stepped down from the mission after being appointed the Delaware agent in 1864 (Weslager 1972:370, 384-385). The Methodists were the first to establish a mission on the Delaware Reserve. In 1832 the Methodists built a church and school five miles north of the old Delaware Crossing, and soon the Christian Church community was established. Captain Ketchum, the first Christian Delaware chief, was converted in this church and is laid to rest at the Christian Church cemetery (Weslager 1972:388). The Moravians of United Brethren were the last to build, constructing their mission in 1837 on the north bank of the Kansas River near the town of Munsee. Not surprisingly, the congregation was mostly Munsee and included a few Stockbridge families as well (Weslager 1972:384). These Baptist- and Methodist-based Delaware communities held together in the removal to Indian Territory while many of the Moravian Christian Delaware remained in Kansas or moved to the Stockbridge Munsee Reservation in Wisconsin. 10. In Kansas, Captain Ketchum was the first Christian Delaware principal chief but he was also of the Turtle clan and was appointed as principal chief through matrilineal ascendancy even though he was a converted Methodist. Ketchum served from 1849 to 1858 and was succeeded by his maternal nephew and fellow Christian, John Conner, also of the Turtle clan (Weslager 1972:387-390). 11. For the most recent historical treatment of Delaware removal to Oklahoma, see Haake (2001, 2002a, 2002b, 2007). 13. The Delaware Tribe was the first tribe to sign a treaty with the American government, doing so on September 17, 1778 (Weslager 1972:304). 14. On July 14, 1951, the Delaware General Council passed a resolution to formally adopt five named persons, granting them full political and property rights, who were not listed on the 1867 roll but who later joined the tribe in Indian Territory and directly purchased their citizenship rights from the Cherokee Nation (Carrigan and Chambers 1994:36-37). 15. The Osage, Kaw, Pawnee, Otoe, and Missouri are all Central Plains tribes that were relocated to reservations on land ceded by the Cherokee Nation. The only tribe with a reservation on the land formerly known as the Cherokee Outlet is the Tonkawa Tribe, who originally occupied the southern plains of Texas. Brasser, Ted. 1974. Riding on the Frontier’s Crest: Mahican Indian Culture and Culture Change. National Museum of Man Mercury Series, Ethnology Division Paper 13. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada. Carrigan, Gina, and Clayton Chambers. 1994. A Lesson in Administrative Termination: An Analysis of the Legal Status of the Delaware Tribe of Indians. 2nd edition. Bartlesville OK: Delaware Tribe of Indians. Cayton, Andrew, and Frederika Teute, eds. 1998. Contact Points: American Frontiers from the Mohawk Valley to the Mississippi, 1750-1830. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. Conner, John. 1866. Letter to Wm. P. Ross, 9 Dec. Kansas Collection, vol. 10:46-48. Lawrence KS: University of Kansas Libraries. Cranor, Ruby. 1991. Kik Tha We Nund: The Delaware Chief William Anderson and His Descendants. Self-published manuscript. Bartlesville OK: Bartlesville Public Library. Eaton, Melissa Ann. N.d. “Against the Grain: Culture Change, Revitalization, and Identity at Delaware Village, Southwest Missouri 1821-1831.” Ph.D. dissertation, College of William and Mary. Farley, A. 1995. The Delaware Indians in Kansas: 1829-1867. Lawrence: Kansas Historical Society. Goddard, lves. 1978. “Delaware.” In Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast. Bruce Trigger and William Sturtevant, eds. Pp. 213-239. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution. Grumet, Robert S., ed. 2001. Voices from the Delaware Big House Ceremony. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. Hale, Duane. 1987. Peacemakers on the Frontier: A History of the Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma. Anadarko OK: Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma Press. Haake, Claudia. 2001. “Resistance Is (Not) Futile—Two Native American Histories of Change and Survival: Removal of Delawares and Yaquis in the United States and Mexico.” Ph.D. dissertation, Department of History, Bielefeld University, Germany. ———. 2002a. “Delaware Identity in the Cherokee Nation.” Indigenous Nations Studies Journal 3(1):19-44• ———. 2002b. “Identity, Sovereignty, and Power: The Cherokee-Delaware Agreement of 1867, Past and Present.” American Indian Quarterly 26(3):418-435. ———. 2007. The State, Removal and Indigenous Peoples in the United States and Mexico, 1620-2000. London: Routledge. Jennings, Francis. 1975. The Invasion of America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. King, Duane, ed. 1979. The Cherokee Indian Nation: A Troubled History. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. Kraft, Herbert, ed. 1974. A Delaware Indian Symposium. Anthropological Series, no. 4. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania History and Museum Commission. ———. 1977. The Minisink Settlements: An Investigation into a Prehistoric and Early Historic Site in Sussex County, New Jersey. South Orange NJ: Seton Hall University Museum. ———. ed. 1984. The Lenape Indian: A Symposium. Archaeological Research Center, no. 7. South Orange NJ: Seton Hall University Museum. ———. 1986. The Lenape: Archaeology, History and Ethnography. Newark: New Jersey Historical Society. ———. 1996. The Dutch, the Indians and the Quest for Copper: Pahaquarry and the Old Mine Road. South Orange NJ: Seton Hall University Museum. Miller, Jay. 1989. “Delaware Traditions from Kansas, NahKoman to Isaac McCoy.” Plains Anthropologist 34:1-6. ———. 1994. “The 1806 Purge among the Indiana Delaware: Sorcery, Gender, Boundaries and Legitimacy.” Ethnohistory 41(2):245-266. ———. 1997. “Old Religion among the Delawares: The Gamwing (Big House Rite).” Ethnohistory 44(1):113-134. Powell, Gina S., and Neal H. Lopinot. 2003. “In Search of Delaware Town, an Early Nineteenth Century Delaware Settlement in Southwest Missouri.” Unpublished paper in the author’s possession. Schutt, Amy. 2007. Peoples of the River Valleys: The Odyssey of the Delaware Indians. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Thurman, Melburn. 1973. “The Delaware Indians: A Study in Ethnohistory.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara. van Laer, A. J. F., ed. and trans. 1924. Documents Relating to New Netherland, 1624-1626, in the Henry Huntington Library. Henry Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino CA. Wallace, Anthony F. C. 1947. “Women, Land and Society: Three Aspects of Aboriginal Delaware Life.” Pennsylvania Archaeologist 17:1-35. ———. 1956. “Political Organization and Land Tenure among the Northeastern Indians, 1600-1830.” Southwest Journal of Anthropology 13:301-321. ———. 1970. King of the Delawares: Teedyuscung, 1700-1763. Freeport NY: Books for the Libraries Press. Weslager, Clinton A. 1972. The Delaware Indians: A History. New Brunswick N.J.: Rutgers University Press. ———. 1978. The Delaware Indian Westward Migration. Wallingford PA: Middle Atlantic Press. ———. 1986. The Swedes and the Dutch at New Castle with Highlights in the History of the Delaware Valley, 1638-1664. Wilmington DE: Middle Atlantic Press. White, Richard. 1991. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Zeisberger, David. 1910. David Zeisberger’s History of the North American Indians. Archer Butler Hulbert, ed. William Nathaniel Schwarze, trans. Columbus: Ohio State Archaeological Society.

3. CHEROKEE NATION, 1870: The Cherokee Treaty lands in the West and the dates that such lands were transferred to other Indian tribes or the U.S. government, or lands on which the Delaware and Shawnee had settled by 1870. Adapted from Duane King, “Cherokee in the West: History since 1776,” in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 14: Southeast, ed. Raymond D. Fogelson and William Sturtevant (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004), p. 355, figure 1. Map by Rebecca Dobbs. ENDNOTES

REFERENCES

D5 Creation

D5 Creation