News Item

now browsing by category

Oklahoma Artists Honored

Oklahoma Artists Honored with Native Arts and Cultures Foundation Fellowships

VANCOUVER, Wash., (Nov. 7, 2013) – From a national call for entries to American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian artists, the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation (NACF) has awarded 2014 NACF Artist Fellowships to three Oklahoma artists.

Writer Eddie Chuculate (Muscogee Creek/Cherokee) of Muskogee, Okla. received a 2014 NACF Literature Fellowship. Renowned basket-weaver Shan Goshorn (Eastern Band Cherokee) of Tulsa, Okla. is a 2014 NACF Traditional Arts Fellow and poet Santee Frazier (Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma) of Syracuse, N.Y. received a fellowship in literature.

Left to right: Eddie Chuculate (Muscogee Creek/Cherokee), Shan Goshorn (Eastern Band Cherokee), and Santee Frazier (Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma)

The three talented artists are among 16 American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian artists selected by the foundation to carry this honor in 2014. Each year, the Native-led arts foundation awards fellowships to recognize exceptional Native artists who have made a significant impact in the fields of dance, film, literature, music, traditional and visual arts. Chuculate, Goshorn and Frazier are the first Oklahoma artists to be awarded NACF Artist Fellowships.

For 2014, the foundation awarded $220,000 to support individual artists through NACF Artist Fellowships ranging from $10,000 to $20,000 per artist. “It is our honor to present a dynamic new cohort of NACF Artist Fellows for 2014,” said NACF Program Director Reuben Roqueñi (Yaqui/Mexican). “Native artists are taking leadership in addressing critical issues across the country and act as catalysts for change in our communities. The fellowships support these artists as they delve deeper into their practices and cultivate their artistic voices to transport and inspire us. Join us in celebrating their adventurous and creative spirits.”

2014 NACF Artist Fellows:

- Keola Beamer (Native Hawaiian), Lahaina, Hawaii, Music Fellowship

- Raven Chacon (Navajo), Albuquerque, N.M., Music Fellowship

- Eddie Chuculate (Muscogee Creek/Cherokee), Muskogee, Okla., Literature Fellowship

- Kaili Chun (Native Hawaiian), Honolulu, Visual Arts Fellowship

- Santee Frazier (Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma), Syracuse, N.Y., Literature Fellowship

- Jeremy Frey (Passamaquoddy), Indian Island, Maine, Traditional Arts Fellowship

- Shan Goshorn (Eastern Band of Cherokee), Tulsa, Okla., Traditional Arts Fellowship

- Melissa Henry (Navajo), Rehoboth, N.M., Film Fellowship

- Micah Kamohoali’i (Native Hawaiian), Kamuela, Hawaii, Dance Fellowship

- Billy Luther (Navajo/Hopi/Laguna), Los Angeles, Film Fellowship

- Patrick Makuakāne (Native Hawaiian), San Francisco, Dance Fellowship

- Nora Naranjo-Morse (Tewa-Santa Clara Pueblo), Espanola, N.M., Visual Arts Fellowship

- Da-ka-xeen Mehner (Tlingit/N’ishga), Fairbanks, Alaska, Visual Arts Fellowship

- Israel Shotridge (Tlingit), Vashon, Wash., Traditional Arts Fellowship

- Brooke Swaney (Blackfeet/Salish), Polson, Mont., Film Fellowship

- David Treuer (Ojibwe), Claremont, Calif., Literature Fellowship

Since 2010, the foundation has supported 85 Native artists and organizations in 22 states, awarding $1,602,000 in assistance, including an award to the Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries and Museums of Oklahoma City. The generosity of arts patrons, the Ford Foundation and Native Nations allows the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation to support the vibrant arts and cultures of American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian peoples. To read more about these three Oklahoma artists and all the talented 2014 NACF Artist Fellows, visit: www.nativeartsandcultures.org.

An open letter to the people of Kansas

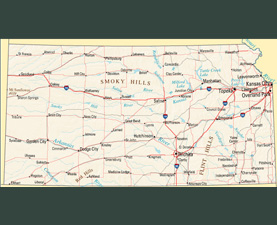

In recent months there has been much speculation as to what the Delaware Tribe’s intentions are with respect to our ever increasing presence in the state of Kansas, our treaty-promised “forever home.”

While I come from a long-standing position to not report anything till I have something to report, it’s clear that speculation has taken over our reason, our history and our intentions, so it is with some legitimate hesitation that I break our silence on the question because I am concerned our efforts will be aborted due to fear and speculation.

Historic Connections

Historically known as the Grandfather tribe by other tribes, our Tribe signed the first treaty with the United States, in our final set of treaties with the United States, we were placed in Indian Territory, (now known as Oklahoma) to exist within the boundaries of another tribal nation, the Cherokees. For much of the time since, efforts to remain a solid, sovereign nation has been a generational fight. A fight for our culture, our language our heritage and ultimately our existence as a people.

After nearly 150 years of litigation and conflict with the U.S. and the Cherokee Nation (one of the largest tribal nations in the United States), history proves the Delaware Tribe has never been afraid of long odds or ever be known to shrink from a fight that seeks to eradicate us from history. Our right to function as any other federally recognized tribe will never occur under the jurisdiction of another tribe in Oklahoma.

Delaware’s Right to Exist

The Delaware’s only seek to exercise the same benefits of tribal sovereignty that every other tribe in the U.S., including the four tribes within the state of Kansas, currently enjoys. While our expressed intentions have never sought to threaten the sovereignty of another tribe in requesting a service area in Kansas, nor do we wish any harm or detriment to any local government or the state of Kansas with our presence. Our intention is to bring more services to an area that could help those that currently go without and to add to existing services that already are underfunded. The proposed area is carefully chosen, not only to reflect our current presence, our concentration of population of Tribal members but also not to infringe on the jurisdiction of the tribes who comprise the “Four Tribes” in Kansas.

Even the most objective observers of federal Indian policy have concluded that federally recognized tribes have been lied to, cheated, assimilated and have had their tribal cultures, traditions and land holdings virtually destroyed by U.S. policies in the past. As improved as things may appear today, those same observers have concluded the Delaware Tribe of Indians have never benefited from current policies that are in place today to help restore tribal governments.

Every Tribe’s Right to Pursue Gaming

Some allege the ONLY reason the Delaware Tribe is engaged in moving to Kansas is to build a casino and are the puppet of greedy gaming developers who are hiding behind the pretense of tribal sovereignty to engage in what some people call, “reservation shopping.” While we may bristle at the notion of such a charge, let me address it head on because it’s important for us to convey we are guided by principle more than any practical economic benefit that every tribe is entitled to pursue.

Since the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988, federally recognized tribes have the authority to enter into the gaming business. In all the years the federal government has tried to reverse the poverty on tribal lands and help tribes overcome their own unique problems, no other law passed by Congress has done more to help tribes have the resources to help save their communities and reinvest in the educational and quality of life issues of our people than the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act.

No tribe would ever take gaming off the table as a viable option as long as it is legally available. This isn’t new or unique to Kansas; actually the Kansas Tribes have done so, as well as the state of Kansas when they licensed their own private casinos and lotteries. However, the legal process is lengthy and complicated. The Wyandottes are an example of a tribe who persevered through the process and even though the federal law was less restrictive at the time, the downtown Kansas City casino was in litigation for nearly two decades.

We are a people true to our word, regardless of the outcome of a tribal election, the principles of keeping our commitments even those that are inherited by our predecessors such as an agreement with a gaming developer will and are still binding on the Tribe, regardless of who the Chief is at any one time. Gaming is nothing more than a means to an end, which provides our Tribe the resources to strengthen our community and bring up the lives of our people.

As the elected representatives of our people, we have sworn to protect the interest of the Delaware people engrained in our tribal constitution. This oath is no less important than the one elected representative of other tribes hold to, or state officials or the elected officials of our federal government. As a government we have engaged in or attempted to engage in government-to-government conversations with other tribes, local government and federal officials in our decision to expand our presence in Kansas.

Delaware Vision: Partnerships through Collaboration

The Delaware Tribe of Indians has a profound vision for our future in Kansas. With respect to other activities within the state’s borders’ we are actively in conversations with the state and local governments as well as federal agencies that hold a trust relationship with the Delaware Tribe to establish a service area. This is not a request for a reservation, nor is it taking lands off the tax rolls, nor is it designed to threaten anyone’s property rights. The designation is awarded to tribal nations who demonstrate a historic connection to the area and the capacity to render federal services that Indian people are eligible for in these areas. Such as agriculture, law enforcement, road and bridge improvements, health care just to name a few. In our proposed service area, there are nearly 50,000 Native Americans eligible for but without access to such services because no tribe serves the area.

The expansion will allow the Tribe to deliver services not only to our own tribal members but also members of other federally recognized tribes who are eligible for federal services but do not live on one of the four tribe’s reservations (the areas in which they serve). The designation will reduce the burden on local and state governments and allow the state’s money to go further for all Kansas citizens. Aside from social and infrastructure services, the Tribe is focused on the economic impact to communities through job creation, support of small businesses and investment in community projects. The Tribe does not outsource jobs we create to China or India. A local tribe in your area with a spirit for partnership and community collaboration is like having both a corporate and governmental presence that creates services, jobs and economic opportunity.

The process for our expansion is unprecedented. We move forward in a good way, slowly and deliberately. The end goal of the Tribe to be actively engaged in many counties and communities as a full-range service provider to all Kansas Native Americans not living on a reservation will take time to realize. But to the Delaware Tribe, time is on our side, because we never, never, never give up,

Wanishi,

Chief Paula Pechonick

Delaware Tribe of Indians

Note: Painting on the home page accompanying this post is titled The Last Removal, by the Lenape artist Jacob Parks (1890-1949), which depicts a Lenape family leaving their home on their reservation in Kansas in 1867.

Historic Preservation Department Visits East Coast Museums

Staff of the Delaware Tribe Historic Preservation Office have recently returned from a grant-funded trip to several museums on the East Coast to document holdings for an upcoming repatriation under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). DTHPO Director Brice Obermeyer and tribal archaeologist Greg Brown visited the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton, New Jersey and the State Museum of Pennsylvania in Harrisburg, PA, as well as working on other historic preservation activities at Morristown National Historical Park in Morristown, New Jersey and Pennsbury Manor in Morrisville, PA.

Dr. Dennis Wiedman Visits Tribe

Dr. Dennis Wiedman, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Florida International University, once again visited the Delaware Tribe on July 17 and 18. He is in Oklahoma doing research on the difficulty Indian people had in being able to continue the use of their sacrament in the Native American Church.

Dennis first came to Oklahoma in his late teens in the late 1960s. His first trips were financed by selling beads and other supplies to Indian people and in turn buying Indian-made goods to take back to Florida. One of the main people Dennis worked with was tribal elder Nora Dean of Dewey, Oklahoma. He was also given a great honor by being taken as a son by tribal member Charlton “Steve” Wilson, and he later served as a pallbearer at Steve’s funeral.

Over the years from studying Native American Church practices and working closely with Nora he began to notice the disastrous effects of diabetes on the native population. He then began his study into diabetes and the Indian people, receiving his Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Oklahoma for his work on Indian diabetes. He continues to research and write articles on Native American health.

During his visit to Delaware tribal headquarters he met with Chief Paula Pechonick with whom he discussed his past work with tribal elders.

- Dr. Dennis Wiedman with Chief Paula Pechonick.

Dennis also met with Tribal Archivist Anita Mathis, and contributed a number of his articles to the tribal library, and with Tribal IT Director Greg Brown to discuss distance-learning class procedures.

- Meeting with Tribal Archivist Anita Mathis.

During his visit he was able to connect with Housing Inspector Walter Dye, an old friend, to discuss people they both knew who were Native American church participants. He also chatted with Bonnie Thaxton, Mary Watters, and Jan Brown.

- Jim Rementer and Dennis Wiedman at Nora Dean’s home in 1970.

Dennis commented on how glad he was at the warm reception he received by present tribal leaders and compared it to the warm reception he had from the previous generations during his years of study here in Oklahoma. We hope to see him back here soon.

–Contributed by Jim Rementer

Purchase of Property in Lawrence, KS

On July 10, 2013 The Delaware Tribe of Indians, through its wholly owned business subsidiary LTI Enterprises LLC, purchased approximately 87 acres of agricultural land in Lawrence, Kansas. The Delaware Tribe had a historic presence in the area, residing on a reservation between Lawrence and Leavenworth between 1830 and 1866. The federal government forced a move of the tribe to Oklahoma after the Civil War. The Lawrence property is seen as an investment in the future as the tribe promotes its theme of “Return to Kansas.”

The federally-recognized Indian tribe has offices in Bartlesville and Chelsea, Oklahoma and also Emporia and Caney, Kansas. They provide government and social services to their members and other Native Americans. Tribal leaders are expanding their service area to provide more social and economic benefits to the state’s American Indian population. Future plans include housing, child care, and a medical clinic.

For more information please send all inquiries to: tribe@delawaretribe.org.

July 23, 2013

Press Statement, Delaware Tribe of Indians

Regarding purchase of property in Lawrence, KS

Sculptor Chris Booth Visits Tribal Headquarters

- Renowned New Zealand sculptor Chris Booth visited Tribal Headquarters in early July to discuss an upcoming commissioned sculpture for the Storm King Art Center in southern New York (http://www.stormking.org/). Here he is with Tribal Archivist Anita Mathis and Chief Paula Pechonick.

- For more information about Chris Booth’s work, go to his web site at http://www.chrisbooth.co.nz.

National Register Nomination for Delaware Town in Missouri

We are pleased to announce that we will soon be nominating the Delaware Town site (23CN1), located near Springfield, Missouri, to the National Register of Historic Places. You may remember from earlier issues of this newspaper that the Tribe has collaborated with archaeologists from Missouri State University to further more than ten years of excavations and surveys of the area. The information gained from excavations at Delaware Town will significantly contribute to our understanding of our Delaware and national heritage, as it represents the only archaeological excavation of a residence associated with the Delaware occupation in the Missouri Ozarks. This site is situated within the historical context of the early movements of the Delaware and other Eastern Woodland tribes to regions west of the Mississippi River in order to continue their traditional lifeways away from the bloodshed and missionary efforts that were increasingly present on the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes frontiers following the American Revolution.

According to the historical literature, some Delaware groups first began moving into the Ozarks, along with other groups of their Shawnee, Kickapoo, Piankashaw and Peoria allies, in the 1780s. They first established villages in the eastern Missouri Ozarks. These Delaware and Algonquin immigrants were slowly pressured to points further west as American encroachment and harassment substantially increased west of the Mississippi following the Louisiana Purchase and the War of 1812. As these allied groups moved into the western Missouri Ozarks, the so-called main body of Delaware who had remained along the White River in Indiana agreed to the Treaty of St. Mary’s, 1818, in which they ceded all land in Indiana in exchange for “a country to reside in, on the west side of the Mississippi.” Then-Missouri territorial governor William Clark assigned the Delaware lands in southwest Missouri on the eastern border of the Osage Reservation. It was at the Delaware Town site that the Indiana Delaware and the Ozark Delaware coalesced in a linear riverine village along the James River from 1820 to 1822, and remained there until leaving for their Kansas reservation in 1830. During these years, Delaware Chief William Anderson, who had risen to prominence amidst the nativistic revivals in the Indiana villages, was looked to as the principal spokesperson for the newly-coalesced James River Delaware. Anderson also provided leadership for the neighboring Shawnee, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Peoria villagers who settled in and near the Delaware reservation and subordinated themselves to them, whom they still considered as their “Grandfathers.”

The Delaware Town site is the archaeological remains of what was once a residence associated with this last Delaware and multi-tribal settlement present along the James River from 1821 to 1830. Delaware Town can thus significantly contribute to our understanding of this important but underrepresented time period in American history. Current information about this time period is based largely on the archival record and historical publications that have interpreted such collections. I am not aware of any archaeological interpretations that have been produced based on the material culture from these Eastern Woodland settlements beyond the survey reports and conference papers that have come from research on the Delaware Town site. Although the Delaware Town site and others like are known and documented, their presence and significance may be underrepresented in the historical and archaeological record due to the often transient nature of these sites (often occupied for a decade or less) and their close similarity in material culture with other, non-Indian, historic-period frontier settlements. Documenting and preserving the Delaware Town site and emphasizing its veiled uniqueness, can thus significantly contribute to our knowledge of the Ozark region’s history. It is the only site of which I am aware that has yielded both archaeological evidence of the experience of Delawares and allied Algonquins in the Ozark region.

The value of this work to the Tribe is that it helps preserve this important component of Delaware history. Archaeological sites are destroyed every day when they are not actively protected. Once successfully added to the National Register of Historic Places, the Delaware Town Site would enjoy further protections under federal law from potential development that is currently threatening the integrity of the site. Who knows what we will learn from this site if it is preserved for the future?

49th Annual Delaware Powwow, May 24-26, 2013

The 49th annual Delaware Powwow was held May 24-26, 2013 at the Falleaf Powwow Grounds near Copan, OK. We hope you all had a good time and will return next year for the historic 50th Annual Powwow!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Top row, l-r: Orange Fancy Dance featuring Jake Lawhead; tribal member Anna Pechonick; tribal member Bear Thompkins; tribal member Bucky Buck; Delaware War Mothers Princess Hayden Griffith. Bottom row, l-r: Delaware Color Guard; Kara House and Vincent Jackson leading the two-step; Grand Entry with Bruce Martin, Chief Pechonick, Jimmie Johnson. |

|

| 2013 Powwow Princess Dava Daylight. |

Dedication of the Social Services Building, May 22, 2013

On Wednesday, May 22, the Delaware Tribe of Indians proudly officially opened its new Social Services Building at 166 NE Barbara on the Tribe’s Bartlesville campus. Former chief Dee Ketchum performed the smoke-off ceremony, after which Chief Pechonick and the other members of the Tribal Council were joined by Bartlesville Chamber of Commerce officials for the ribbon-cutting.

We invite tribal members and others to visit this new facility, which includes our Housing, Social Services, Education, and Environmental Programs as well as the Library, Museum, and Archives.

We also want to acknowledge our new Memorial Garden north of the pond across the street from the Social Services building. Thanks to tribal employee Gina Roth and her son Trey for their hard work getting it set up.

|

|

| Former chief Dee Ketchum burns cedar and offers a prayer at the dedication. | Chief Pechonick cuts the ribbon. |

|

|

| Tribal Manager Curtis Zunigha, Chief Paula Pechonick, and former chief Dee Ketchum after the ribbon cutting. | Chief Paula Pechonick and Jim Gray. |

|

|

| Chief Pechonick with representatives from Cherokee Nation. | Councilwoman Janifer Brown gives Lee Keener and Jack Baker of Cherokee Nation a tour of the new kitchen. |

|

|

| Tribal Archivist Anita Mathis with Debbie Neece and Joan Singleton of the Bartlesville History Museum. | Coke Meyers, a relative of Will Rogers and the oldest member of the Washington County Historical Society, with its youngest member, Social Services Manager Lacey Harris. |

|

|

| Chief Pechonick addresses the crowd. | Tribal elder Jack Tatum enjoys the new Memorial Garden. |

D5 Creation

D5 Creation