Culture-SubPage

now browsing by category

Lenape Pottery

- Pottery — The Lenape made cooking pots and other vessels out of clay. In this photograph the small pot on its side is the normal size cooking vessel. The large pot holds about twenty gallons and may have been used for some type of ceremonial event.

- Photgraph courtesy of Herbert C. Kraft

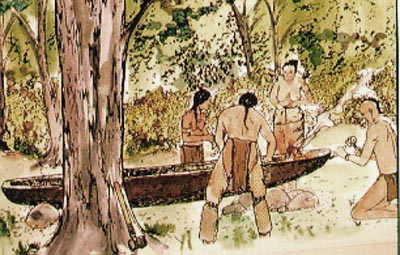

Lenape Canoes

- The Dugout Canoe — Canoe travel on rivers, lakes and possibly the ocean provided the principal means of transportation. There were no beasts of burden in North America and it is not certain if the Lenape people used their dogs to carry things as some tribes did. What had to be transported was carried on people’s backs or in canoes. Canoes were made from the trunks of trees such as tulip tree, elm, oak, or chestnut. In fact the Lenape name for the tulip tree is Muxulhemenshi, “Tree from which canoes are made.”

Birch bark canoes were not used in the Lenape homeland because the type of birch growing there is not suitable for canoe making. In this illustration, a tree is being felled by means of fire set against the base of the trunk. Wet deerskin has been wrapped around the trunk to keep the fire from spreading upwards. From time to time the fire will be doused and the charred portions adzed away. By repeating this process the tree is finally burned through and falls for lack of support. In making a dugout canoe, a suitable tree trunk is selected and one side is adzed flat. Small fires are set to burn into the trunk, thus helping to hollow it. Charred parts are adzed or gouged out and the hull is finally planed smooth.

Birch bark canoes were not used in the Lenape homeland because the type of birch growing there is not suitable for canoe making. In this illustration, a tree is being felled by means of fire set against the base of the trunk. Wet deerskin has been wrapped around the trunk to keep the fire from spreading upwards. From time to time the fire will be doused and the charred portions adzed away. By repeating this process the tree is finally burned through and falls for lack of support. In making a dugout canoe, a suitable tree trunk is selected and one side is adzed flat. Small fires are set to burn into the trunk, thus helping to hollow it. Charred parts are adzed or gouged out and the hull is finally planed smooth.- Illustration courtesy of Herbert C. and John T. Kraft

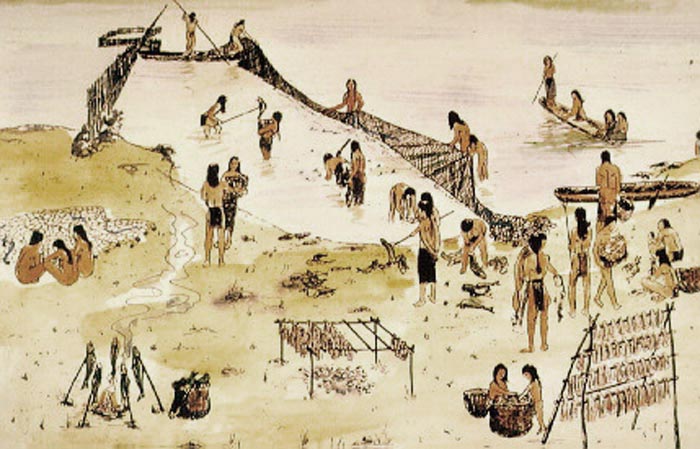

Lenape Fishing

- Shad Fishing in the Delaware River — A fishweir consisting of wooden stakes arranged in a fence-like manner, and a weighted fish net, are being used to gather the shad so that they may be easily speared, or caught with bare hands. A previous catch of fish has already been gutted, split and placed near a fire-hearth and over racks to dry for storage. Anadromous shad swim up the major rivers by the millions in March and April to spawn in freshwater streams. Abundant fish enabled the Lenape to congregate in larger numbers than usual, and to remain at one site for a longer time.

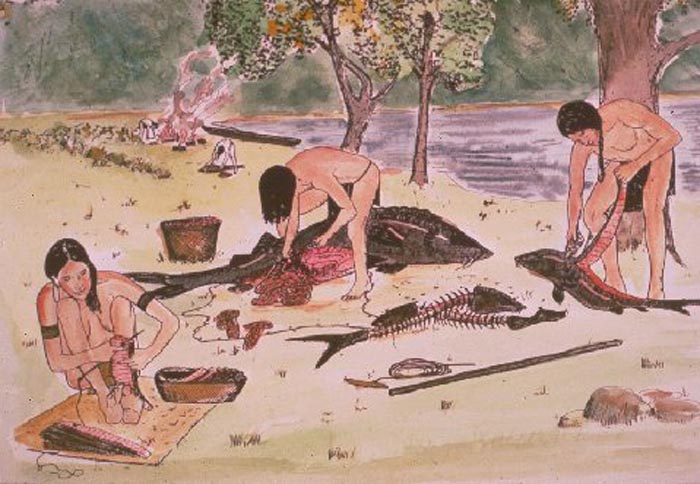

- Fishing for Sturgeon — While two men use large chipped stone knives to remove the scutes (the bony plates on the back of the sturgeon) and cut the meat, another worker thrusts a long copper or bone needle and line through prepared slices of fish. The skewered flesh will be hung up to dry. Other workers use large pottery vessels and heated stones to cook oil out of the fish heads and skeletal parts. Sturgeon weighing up to two hundred pounds and more, and measuring over six feet in length, were harpooned and caught in nets. These anadromous fish came from the ocean into the Delaware and Hudson rivers to spawn in freshwater streams.

- Illustrations courtesy of Herbert C. and John T. Kraft

Lenape Stories

WHY THE RACCOON HAS MARKS ON HIS FACE

This is about the little raccoons and what they said caused them to have little marks on their eyes. They said that the other creatures told him to go and borrow some firewood from the camps around. So this coon then went to the camps to get some firewood sticks that were already aflame and blackened by the fire and burned on part of the stick. And they said his little coon fell down with these in his hand and his face fell across these charred sticks. And that’s why now he has little marks to show his shame trying to steal something from the campers. That is the thing to tell the younger generation to not to steal anything because that mark will be upon you.

KWËLËPISUWE . . . A HUMOROUS TALE

I heard this story a long time ago when I was a young woman. At one time there was a man named Kwëlëpisuwe. It is said that he liked women. When he learned where some women lived he would go there immediately. At first it seemed like he just wanted to visit, but he must have wanted to flirt.

He would suddenly stand up and reach into his pocket [and] take out some finger-rings. He stood there. In his hand he held the rings. He said, “I will burn them, I will burn them!”

Then the women would all get up. They began to beg him and they hugged him and they rubbed him. They said, “Don’t! Don’t! Give them to us, give them to us.”

The man would just have a smile on his face. He put the rings back in his pocket, he left. He went looking for some other women so that he could flirt [again].

It is said that the man would say, “I am really good looking! All the women like me! Oh, the women bother me, even when I am trying to sleep.”

Finally that man was hated because he admired himself. Everyone hated him, even women, men, children, and even dogs.

This comes from a correction of long ago, “A person should not brag about himself,” the elders said. Then I asked my father, “Was that really true that he was handsome?” My father said, “That wasn’t so, the man was homely. He just said that.”

WHAT THE RABBIT SAID

This is a story about Rabbit who used to make a lot of stories long ago. When animals had a council long ago, they would have a council and talk about something. Every kind of animal was there including deer and buffalo.

The Rabbit would be asked, “What’s the matter with you? Your shoulder blades really stick way out when you sit down?”

He said, “That’s right, I had two wives long ago. I used to sleep between them. That’s why when I used to sleep they really crowded me, that’s why my shoulders are like that.

And they asked him again, “How come those ears of yours are so long?”

He said, “Well, I was a chief’s messenger, long ago. I would be made a chief’s messenger all the time. “I delivered some messages to all these different kinds of animals,” he said. That is what the one called Rabbit said. He said, “That’s really true. That’s how come my ears are long, so that I will hear anything well. I don’t want to miss hearing anything because I want to deliver the message to them, to animals of every kind, when the chief hires me, when he makes me his messenger.

That’s the reason why I would want to hear things well.” That’s why his ears are long, because he always wanted to hear things well.

When the animals would assemble in council, they would talk about when they hide from people. The buffalo said, it’s hard for us, because we’re big. We have to flee to where there’s thick brush, and we are able to hide. And that deer said the same.

And then the rabbit jumped up. He said, “Well, for me, though, it’s easy to hide from anybody. On the hillside, in the grass, all I have to do is make a hole, and that’s where I back in. That’s how I hide from anybody. Sometimes someone comes close by, and he doesn’t see me,” said that rabbit.

STORY OF A LENAPE BOY AND A MOTHER BEAR

There’s an old story that my parents used to tell me about how a boy got lost in the deep forest one time, way back there. He was a little kid, and finally he met this mother bear. I guess he went kind of irrational, sort of lost his mind, and he thought this bear was his mother. The way she looked to him she had this apron on like the old Delaware women used to wear. She had some little cubs with her that he thought were children and she took him in the den with her and she just licked him and he nursed her like she was his mother, and he ate honey. He said he talked with her.

There were some hunters came into the woods and killed her and they said he just grieved over her because he really thought that was his mother. They said he really grieved when these hunters killed her, and he grieved a long time for her. They say that’s the only mother he ever knew.

I don’t know if this is Delaware mythology or whether this is supposed to really have happened, but anyway that is a story that was told to me.

GIVE US A LITTLE PIECE OF YOUR LAND

Our elder brothers’ tribe (the Europeans) wanted to fool us when they were new here. They said, “We will really treat you good for as long as the river flows and the sun always moves, and as long as the grass always comes up in the Spring then I will take care of you. That will be for how long I will be a friend to you all,” he said. He wanted to fool us and it seems he is still fooling us.

Then he said, “Here, I will give you this red flag.” He said, “As long as you keep it you will give us a little piece of your land as much as a cow we will kill. Then we will kill him and skin him. Then they did not take the hide off but cut it into very small pieces. Then they [the Delawares] looked good at it. It was a big piece of land our Lenape ancestors of long ago gave to them. Then they said, “Oh my!” They said. They thought that the land was only to be as big as the hide they put on the ground but it was a big piece. Then they said, “You didn’t say, ‘I want to cut it’.”

He said when he had already finished, “You finish signing on this paper.”

It was said at that time we will treat you good. You will be given everything. That is really true, he gave us everything. Then they gave those late chiefs an axe and a hoe so they could use them. Then they (the chiefs) just hung them on their necks.

[This might sound like a strange thing to do but in those days the ax heads and hoe heads were much smaller and the early Lenape probably thought they looked like some type of pendant, especially since they were not hafted so they did not come with a handle attached].

Then the white man told them, “No, that is not the way to use them when you wear them on your neck. I will give you something different to wear on your neck, that’s it. Then he handed them back, and he accepted them. Then he put them on handles, whatever it is so that can take ahold of this. Then the white man said, “This is how it is done when you plant or when you hoe. Now this axe for you cut trees or for cutting wood or to make or to make a log house. That is what it is used for.

Then he said, “All right.” Then they always made use of them. That is what I told my daughter and my grandchildren, “They are still fooling us.”

WHEN SQUIRRELS WERE HUGE

It is said that long ago the squirrel was huge, and he walked all over the place, in the valleys, in the woods, and the big forests. He looked for creatures that he could eat. He would eat just anything, animals, even snakes.

Suddenly one evening he saw a two-legged creature running along. So he ran after that two-legged creature, and finally he caught that person, and when he snatched him up he began to tear him to pieces. Finally he ate that person all up except for the person’s hand which the giant squirrel was carrying in his hand.

While he was still busy chewing, all at once this person, an enormous person, was standing nearby. That person had a very white light shining and shimmering all around him, and when he said anything he roared like thunder and the earth shook and the trees fell down. He was the Creator.

The Creator said to the squirrel, “Now, truly you have done a very terrible deed. You have killed my child. Now, from this time on it is you who will be little and your children and your great grandchildren will be eaten, and the shameful thing you did will always be seen (by a mark) under your forearm.” Oh, the squirrel was scared, and he trembled with fear. He wanted to hide the man’s hand, and he placed it under his upper arm. This story must be true because for a long time I have cut up and cooked many squirrels, and I have seen the hand under the squirrel’s upper arm. We always cut that piece out before cooking the squirrel.

THREE BOYS ON A VISION QUEST

There were once three Lenape boys who were sent on a vision quest. A Manitu came to them and asked what they would like to be when they grew up.

One boy said that he would like to be a hunter. Another said he would like to be a warrior. The last one said he wanted all the women to like him.

When they grew up, that came to pass. The one boy was a fine hunter. The other was a good warrior. But the third one, who wanted all the women to like him, was killed by a bunch of women at a gathering who ganged him and tore him to pieces because each one wanted him. He should only have asked for one woman to like him.

There are two morals to this story: One is to not be greedy when you ask for something, and the other is to not ask to be more than you can be.

THE MAN WHO VISITED THE THUNDER-BEINGS

Once a man wanted to go and visit with the thunder beings. He told the men all over the village, “I wish you would all help me, I want to cut some wood. I want to heat this boulder.” Everyone came there, and there were many of them who cut wood, and finally they had a lot of wood. Then they began to heat the big rock. When it got very hot, they pushed it into the big river. Then when the steam arose the man jumped into it. He went up to where the thunder beings live.

Oh, the man was well received by the thunder beings. One told the man, “I am glad because you came here where we live. Soon we will eat.” Finally when it got to be evening, the thunder beings began to gather some bones. The bones were dry, and white, and old. They used them when they made soup. He said that the soup looked good.

The one old being told the man, “You people might hear us sometimes.” Soon after the old being said that he heard them, but when those young thunder beings make a noise it is loud and they are heard when it is going to rain. The old thunder beings made a low rumbling noise. After the man had visited the thunder beings for several days, he told them, “Now I will be going home.”

Then when a little cloud floated by near where he was standing he jumped onto it. The man went home and he notified everyone and they held a council. He said, “Here is what the thunder beings told us.” Everyone was surprised when the man told the story.

THE GOOD LOOKING WOMAN

Once there was a good looking woman. The men all liked her looks, but she would not have any of them. Even several animals said of her, “I sure would like to go with this woman.”

Now there were three animals: a beaver, a skunk, and an owl. They said, “Now we will try to get this woman.” They told the owl, “You go first and see whether you can get this woman.” Then the owl went to see the woman, but she told him, “I won’t go with you because you are ugly. Your eyes are too big. I won’t go with you!” So the owl went back and said, “I couldn’t get that woman.”

Next the skunk went to see the woman, and she told him, “I won’t go with you either because you are too ugly, and you stink.” So he went back and said, “I couldn’t get that woman either.”

So then the beaver said, “I will go see that woman.” When he got there he began to talk to the woman, but he also failed to get the woman. She told him, “I won’t have you because you are an ugly thing. Your teeth are wide and your tail is big and broad. That tail of yours looks like a stirring paddle.”

Then the beaver went back and he said, “Well, I also could do nothing with that woman. Now I wonder what we could do to get that woman?” Then they talked about what they could do to be able to get that woman. The beaver said, “Way over there in the creek, where she gets water, there is a log that runs into the water. Now I’ll go and gnaw that log nearly in two. Then when that woman goes to fetch water, her weight will break the log, and the woman will fall into the water. Then she will send for us so we can help her get out.

Then when that woman fell in the water she said, “Now I wish the beaver was here. Maybe he could help me out of get out of the water.”

Then she began to sing, “Pe Pe Kwan Sa, Pe Pe Kwan So. Ni ha noliha tamakwesa (I like the beaver).” Then he said, “No one would like my looks because I am ugly. My teeth are too wide, and my tail looks like a stirring paddle.”

Then the woman sang, “Pe Pe Kwan Sa. Niha nolina shekakwisa (I like the skunk). Pe Pe Kwan Sa.” The skunk said, “No one would like my looks because I am so ugly and because I stink.”

Then again she began to sing, “Pe Pe Kwan Sa. Niha noliha kukhusa (I like the owl).” Then the owl said, “No one would like my looks because I am ugly. I’ve got big eyes.”

So the woman floated on down the creek, nobody would help her, and she finally drowned.

THE HUNTER AND THE OWL

Once a Delaware man and his wife went on a long hunt quite a way from the village. They had been out several days without having any luck when one night as they were sitting around their camp fire an owl hooted from a tree near by and after hooting laughed. This was considered a good omen, but to make sure of this the hunter took a chunk of fire and retired a little way from the camp under the tree where the owl was perched, and laid the chunk of fire on the ground, and sitting by it began to sprinkle tobacco on the live coal and talk to the owl. He said: “Mo-hoo-mus (or Grandfather), I have heard you whoop and laugh. I know by this that you see good luck coming to me after these few days of discouragement. I know that you are very fond of the fat of the deer and that you can exercise influence over the game if you will. I want you to bring much game in my way, not only deer, but fur-bearing animals, so that I may return home with a bountiful supply of furs as well as much dried meat, and I will promise you that from the largest deer that I kill, I will give you the fat and heart, of which you are very fond. I will hang them in a tree so that you can get them.” The owl laughed again and the hunter knew that he would get much game after that.

The next morning he arose early, just before day, and started out with his bow and arrow, leaving his wife to take care of the camp. He had not gone far before he killed a very large buck. In his haste to take the deer back to camp so that he could go out and kill another before it got too late, he forgot his promise to the owl and did not take out the fat and heart and hang it in the tree as he said he would do, but flung the deer across his shoulder and started for camp. The deer was very heavy and he could not carry it all the way to camp without stopping to rest. He had only gone a few steps when he heard the owl hoot. This time it did not laugh as it had the night before.

The owl flew low down, right in front of the man, and said to him: “Is this the way you keep your promise to me? For this falsehood I will curse you. When you lay down this deer, you will fall dead.” The hunter was quick to reply: “Grandfather, it is true I did not hang the fat up for you where I killed the deer, but I did not intend to keep it from you as you accuse me. I too have power and I say to you that when you alight, you too will fall dead. We will see who is the stronger and who first will die.” The owl made a circle or two and began to get very tired, for owls can only fly a short distance. When it came back again, it said: “My good hunter, I will recall my curse and help you all I can, if you will recall yours, and we will be friends after this.” The hunter was glad enough to agree, as he was getting very tired too. So the hunter lay the deer down and took out the fat and the heart and hung them up. When he picked up the deer again it was much lighter and he carried it to his camp with perfect ease. His wife was very glad to see him bringing in game. She soon dressed the deer and cut up strips of the best meat and hung them up to dry, and the hunter went out again and soon returned with other game.

In a few days they had all the furs and dried meat they could both carry to their home, and the hunter learned a lesson on this trip that he never afterwards forgot, that whenever a promise is made it should always be fulfilled.

WHY THE WOLVES AND DOGS FEAR EACH OTHER

A long time ago when this world was new these wolves and dogs were friends, but now at this time everything is different. At that time when it got to be wintertime the wolf said, “I am cold, and hungry! Who is there who would go where the humans are to get a stick with fire on one end so we could make a fire?” The little mongrel dog said,

“Oh, my friend, I will go get some fire!” The wolf said, “All right, so be it!”

The little dog went to get the fire saying, “We will soon have a good blazing fire! We will be warm!” So he left and he went near to where the Delawares lived. When he got near, a girl said suddenly, “Oh, there is someone who is very cute! I want to go see him. This is surely the little dog.” The girl began to pet the little dog. She told him, “Come here, come here! You are cold! Soon I will feed you, I will give you meat and bread.”

Oh, the little dog was happy, and he went into the bark house, and he forgot to bring the fire. Finally the wolf gave up, saying, “That ‘old’ dog is a big liar! I will knock him in the head if I ever see him!” That is the reason these wolves and dogs are afraid of each other to this day.

THE FOX AND THE RABBIT STORY

One time a fox lived near a creek. He would always work, and every spring he would make garden, different things; beans, lettuce and corn. Every morning he would go hoe. One morning he saw that everything had been bitten off. He thought, “Someone must like to steal,” and then he went home.

He sharpened some little sticks, he went and drove them into the garden [with the sharpened ends sticking up.] The next morning he went to the garden. There was blood everywhere, and rabbit hairs scattered here and there. The fox said, “See there, now I know who that thief is.”

Then he went to visit the rabbit. He knocked on the door. He heard the rabbit when he said, “Come in! Come in!” The rabbit was lying down. The fox went and sat down. He told the rabbit “Are you sick?”

The rabbit said, “Oh no, I am just resting.” The fox said, “OK, well, let’s smoke.” The rabbit said, “OK, that’s it.” Then he picked up his pipe, he pulled it out.

The rabbit had difficulty getting up. When the fox saw the rabbit he must have had a bloody behind. He immediately said, “See there! You are the one who is stealing from my garden.” The rabbit said, “Not me, not me!”

Finally the fox quickly got mad, they almost fought. He said, “You are the biggest liar! You are shameful!” The fox was so angry and so he went home. It has long been known that the rabbit likes to lie.

Foods Eaten by the Lenape Indians

When we talk about the foods the early Lenape people ate we must remember that there were no supermarkets at which to buy the foods, and there were no refrigerators in which to store the food. The food had to be eaten very soon or it had to be prepared in various ways for storage so it could be eaten later.

Men and boys knew that hunting and fishing were very important. Deer, elk, black bear, raccoon, beaver, and rabbit were among the animals hunted for meat, skins, and sinew, and the bear’s fat was melted, purified, and stored in skin bags. Turkeys, ducks, geese, and other birds were killed for meat and feathers. To prevent spoilage, some meat and fish were smoked and dried in the sun. Dried meat lasted for a long time. Dried meat could be chewed, or it could be cooked in a soup or stew. The Lenape always shared their food so no one ever went hungry as long as there was food in the village.

Birds were hunted, trapped, and their eggs were eaten. Marsh birds such as geese and ducks were killed with bows and arrows. They were also caught in traps and nets. Turkeys were favorite game birds that lived in the forest. Their meat was good to eat, and Indian women liked to make colorful robes and mantles with the turkey’s feathers. They tied the turkey feathers on to a hand-made net backing that was then fastened to a skin cloak worn over the shoulders.

Passenger pigeons were another favorite game bird. Thousands of these birds once flew over the land in great flocks. The Indians caught passenger pigeons in nets. They took the eggs and young squabs out of their nests and ate them too. Later. white hunters killed so many passenger pigeons that they are extinct.

Fishing

Fishing provided much of the food eaten by the Lenape. Some lakes and rivers had fish all year. Other fish such as herring, shad. salmon, and sturgeon spent the cold months in the ocean and returned to the rivers during the spring to lay their eggs. Each year, thousands of shad swam more than three hundred miles from the Atlantic Ocean into the Delaware, Raritan, Passaic, and Hudson Rivers, to lay their eggs. The Indians used weirs or fence like traps and long nets to catch these fish. Some fish were easy to catch, but sturgeon were harder to land because they grew more than six feet long and weighed as much as two hundred pounds or more. Harpoons made out of deer antlers were sometimes used to spear large fish.

Fresh fish were cooked over a fire. The women also wrapped fish in clay and baked them in hot ashes. The clay acted like an oven. When the fish was ready to eat, the clay was broken away and all the skin and scales came off with it. When the Lenape caught more fish than they could eat, they dried them in the sun, or smoked them over a wood fire. This preserved the fish so that they could be stored and eaten at a later time. Fish eggs or roe were a special treat.

Shellfish & Crustaceans

Clams, oysters, and scallops were gathered from the ocean shore and bays, and the Lenape who lived near the shore harvested and ate thousands of shellfish. The Lenape who lived along lakes, rivers and streams, gathered and ate freshwater mussels. Crayfish, a freshwater crustacean that looks like a small lobster, were caught in rivers and lakes, and these were eaten as well.

Wild Plant Foods

Women and children went into fields and forests to gather plants, roots, berries, fruits, mushrooms, and nuts. Most of this food was eaten as soon as it was ripe. Sometimes there was so much plant food that the surplus could be dried and stored for the wintertime. In the spring there were wild strawberries, blueberries, and blackberries. The roots of cattail plants and water lilies were eaten, and persimmons, cranberries, and wild plums were also gathered. Nuts such as walnuts, butternut. hickory nuts, and chestnuts were gathered in October and November.

Oak trees supplied many acorns, but some acorns have a bitter taste. Lenape women discovered that they could remove the bitter taste by roasting the acorns, or by crushing these nuts in a wooden mortar and rinsing them in hot water. These leached acorns could be cooked in a porridge, or pounded into flour to make bread.

Cooking oil was made from nuts that were crushed and cooked in boiling water. The nut oil floated to the top of the water where it was scooped off with spoons or ladles made from turtle shells or clam shells. The nut oil was stored in gourd bottles or clay pots until needed.

Garden Plants

In their gardens the Lenape Indians planted corn, beans, and squash. Sunflowers, herbs, and some tobacco were also planted. Vegetables were eaten as soon as they were ripe, or some were also stored away for the wintertime. Ears of corn were tied in bundles and hung from the ceilings of the houses to dry. Corn kernels and beans were removed and stored in skin bags. Pumpkins and squash were cut into rings. These rings were put on a stick and hung up to dry in the sun. As long as these foods were kept dry, they would not spoil. When a Lenape woman wanted to use dried food, she cooked it in water. The water made the dried food swell up and become soft enough to eat.

Some Lenape also dug deep, wide holes or storage pits into the earth. Dried meat, dried fish, nuts, and other dried foods were placed in these storage pits. Stored foods helped the Lenape survive the cold winter.

Present-Day Foods

Like most modern Americans the Lenape of today eat all kinds of food—pizza, steak, fried chicken, hamburgers, and so forth. There are some special occasions where Indian foods are served, and usually you will find foods like frybread, corn and meat, and grape dumplings.

Recipes

Salpon (Frybread)

Mix the first three ingredients with enough Water until like pancake batter. Let stand a few minutes while heating enough grease for deep-fat frying.

In a large bread mixing pan have more flour. After making a depression in the flour, pour into it some of the mix, and knead it. Knead until about like biscuit dough.

Make round cakes, about 5 inches in diameter and 3/4 inch thick.

Use a “tester” (a small piece of dough) to test the heat of the grease. When hot enough, the dough will first sink, then immediately rise.

When the grease is hot enough, the bread can be fried. Turn it and remove with a spoon or tongs. Never pierce the bread with a fork.

Shëwahsapan (Grape Dumplings)

Place grape juice and sugar in a large saucepan and heat, but hold out ½ cup grape juice as the liquid for the dumplings.

Mix the remaining ingredients until a bit thicker than biscuit dough.

On a floured board roll out four circles each being about 12 inches in diameter and 1/4 inch thick. Cut these into 3/4 inch wide strips, and cut the strips into 3 inch long pieces.

When the Juice is boiling, add the dumplings, one at a time. Boil slowly for about 15 minutes.

Lenape Family

- Interior of a Lenape Barkhouse — This illustration shows a Lenape family inside their barkhouse. A fire for cooking and to provide warmth is burning in a pit in the center of the floor. Decorative mats affixed to the walls offered a measure of insulation. Smoke escaped through openings in the roof which could be covered in time of rain. Braided ears of corn and herbs were hung from the ceiling, and dried foods were stored below sleeping platforms and on shelves over beds. Firewood was usually stored in a compartment at the end of the house to keep it dry and ready for use. Large storage pits were also dug into the earth at the ends of such houses to provide additional food storage, especially in winter when outside storage pits might be snowed over.

- Illustration courtesy of Herbert C. and John T. Kraft

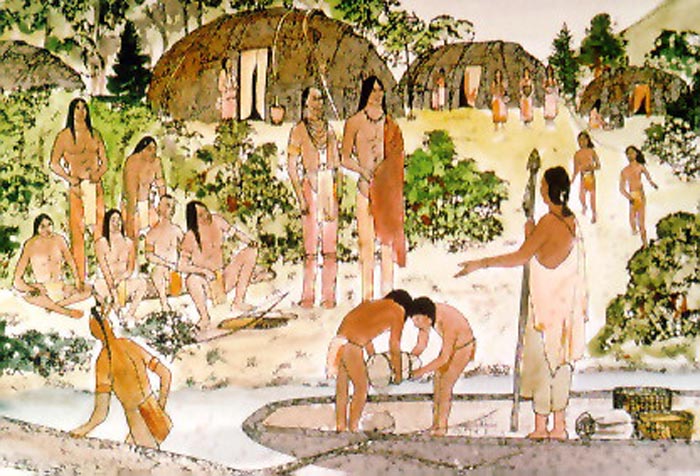

Lenape Villages

- Lenape Village — This scene shows some people arriving at a Lenape village by dugout canoe, and people who live in the village carrying on their daily activities. Perhaps those in the canoe have come to do some trading. In the background can be seen the barkhouses. These were usually made of a framework of cut young trees with the bases buried in the ground and with the tops bent over and tied together. The frames were then covered with sheets of bark, usually elm or chestnut. Lenape villages were not fortified or surrounded by palisades.

- Illustration courtesy of Herbert C. and John T. Kraft

Kokolësh (Rabbit Tail) Game

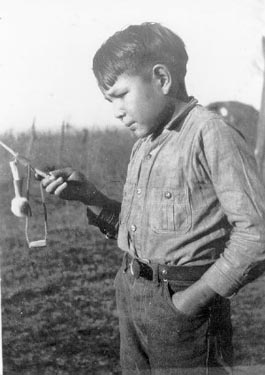

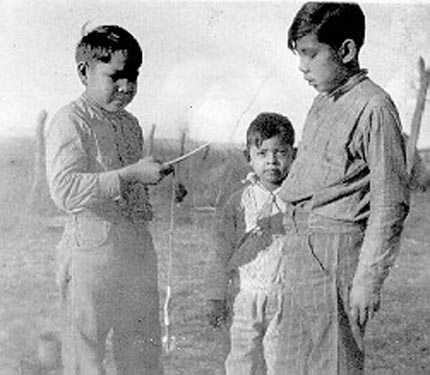

- Warren ‘Judge’ Longbone catches one of the cones on the stick.

- Warren ‘Judge’ Longbone gets ready to try to catch one of the cones in the Kokolësh game. Waiting their turns are Glenn McCartlin and Jim McCartlin.

Pahsahëman — The Lenape Indian Football Game

Based on a paper by Jim Rementer, published in Bulletin #48 of the Archaeological Society of New Jersey (1993) and updated with additional information and photographs for the Tribal website.

It is a beautiful morning in late Spring. The year is 1600. In a large open field near one of their main villages (in an area the white people would later name Philadelphia) the people are playing a game. Laughter can be heard from the participants and spectators alike. The people relish these carefree moments playing their game which they call Pahsahëman. Little did they know as they played the game that four hundred years later their descendants would be playing the same game, however, their location had change because they were now in a far-off land called Oklahoma.

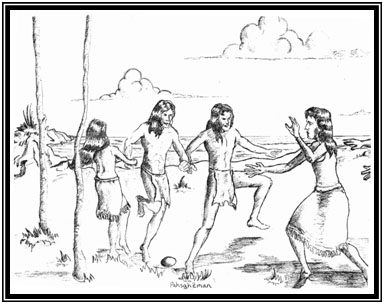

- Scene of a Lenape Football Game as might have been played on a Beach in what is now New Jersey. Drawing by Delaware artist Clayton Chambers

Introduction

The games played by the Lenape or Delaware Indians have not been well documented. When they have been mentioned in the literature, many details of the games are sadly lacking.

The Lenape Indians have long played a version of football which differs markedly from the football game known to non-Indians. In the Lenape football game, men are pitted against the women in a very rough-and-tumble game.

We are giving the rules of the game which were written out by the late Nora Thompson Dean (Touching Leaves Woman) for the Lenape Land Association in Pennsylvania.1 Since the organization no longer exists, this information which was printed in their newsletter in April, 1971, would otherwise be lost.2 We begin with a brief history of the game.

History of the Game

Various forms of football were played along the northeast coast of America. Flannery (1939:187) regards football as one of “forty-three traits [which] may be due to independent invention in the coastal Algonquian region, since they are not characteristic of the Iroquoian, Southeastern, or Northern Algonquian areas.” Football games were also recorded for the Micmac, Abnaki, Malecite, Massachusetts, and Narragansett (Flannery 1939:187). Swanton (1928:707) also says it is “apparently a coastal Algonquian game, not found in the Southeast except among the Creeks.”

Some forms of football were played men-against-men as among the Massachuset in 1634, reported by William Wood (Culin 1901:698). In a number of cases the text does not indicate whether the teams were composed of men only, or men-versus women. A good example is the following brief account by Roger Williams who wrote about “pasuckquakohowauog,” which he translates as “they meet to foot-ball.” He says:

They have great meetings of foot-balle playing, only in summer, town against town, upon some broad sandy shore, free from stone, or upon some soft heathie plot, because of their naked feet, at which they have great stakings, but seldom quarrel (Williams 1643:146).

Some writers (Speck 1931:76 and Goddard 1978:231) claim the Lenape learned this game from the Shawnee. In fact, we have no very early descriptive accounts of the game among the Lenape. Neither do we have any early accounts for the game among the Shawnee, so far as this writer knows.

We know from historical accounts that at least some of the Shawnee arrived in the homeland of the Lenape about the year 1692, and settled near the Delaware River in eastern Pennsylvania (Howard 1981:7).

Thirty-six years earlier, in 1656, Daniel Denton wrote, “Their Recreations are chiefly Foot-ball and Cards, at which they will play away all they have, excepting a Flap to cover their nakedness” (Denton 1670:7).

Unfortunately Denton uses the term “Indians” to describe any and all tribes he met in the area, so we cannot be certain whether the game was used by groups of the Munsee Delawares, or Montauk farther east on Long Island, or both. However, this does tell us that a form of a football game was being played by Delawares or closely related tribes living just north and east of the main body of Lenape at least as early as 1656.

At the Jamestown settlement in Virginia, we find an account of the football game by Henry Spelman. He was captured and raised by the Indians for two years (1609-1610) and later served as interpreter for the colony. In his account of the game, he says:

They [the Virginia Indians] use beside football play, which wemen and young boyes doe much play at. The men never. They make ther Gooles as ours only they never fight nor pull one another doune (Arber 1910:CXIV). [His comment, “The men never,” frequently applies to the game today as most of the male players are older boys and young men.]

Another account written about 1610 from the same area reads:

Likewise they have the exercise of football, in which they only forcibly encounter with the foot to carry the ball the one from the other, and spurned it to the goal with a kind of dexterity and swift footmanship, which is the honour of it; but they never strike up one another’s heels, as we do, not accompting that praiseworthy to purchase a goal by such as advantage (Strachey 1849:77).

After the Denton account, the next account of a Delaware football game was in the 1790s.

The party, however, were received very kindly by the venerable old Delaware chief Bu-kon-ge-he-las, whose name has been given to a fine mill-stream in Logan county. He was one of the chiefs who negotiated the treaty at the mouth of the Big Miami, with General George R. Clark, in 1786, in which his name is written Bo-hon-ghe-lass.

In the course of the afternoon he got up a game of football, for the amusement of his guests, in the true aboriginal style. He selected two young men to get a purse of trinkets made up, to be the reward of the successful party. That matter was soon accomplished, and the whole village, male and female, in their best attire, were on the lawn; which was a beautiful plain of four or five acres, in the center of the village, thickly set in blue grass. At each of the opposite extremes of this

lawn, two stakes were set up, about six feet apart.

The men played against the women; and to countervail the superiority of their strength, it was a rule of the game, that they were not to touch the ball with their hands on the penalty of forfeiting the purse; while the females had the privilege of using their hands as well as their feet; they were allowed to pick up the ball and run and throw it as far as their strength and activity would permit. When a squaw succeeded in getting the ball, the men were allowed to seize —whirl her round, and if necessary, throw her on the grass for the purpose of disengaging the ball—taking care not to touch it except with their feet.

The contending parties arranged themselves in the center of the lawn—the men on one side and the women on the other—each party facing the goal of their opponents. The side which succeeded in driving the ball through the stakes, at the goal of their adversaries, were proclaimed victors, and received the purse, to be divided among them.

All things being ready, the old chief came on the lawn, and saying something in the Indian language not understood by his guests, threw up the ball between the lines of the combatants and retired; when the contest began. The parties were pretty fairly matched as to numbers, having about a hundred on a side, and for a long time the

game appeared to be doubtful. The young squaws were the most active of their party, and most frequently caught the ball; when it was amusing to see the struggle between them and the young men, which generally terminated in the prostration of the squaw upon the grass, before the ball could be forced from her hand.

The contest continued about an hour, with great animation and various prospects of success; but was finally decided in favor of the fair sex, by the herculean strength of a mammoth squaw, who got the ball and held it, in spite of the efforts of the men to shake it from the grasp of her uplifted hand, till she approached the goal, near enough to throw it through the stakes (Burnet 1847:68-70).

When the contending parties had retired from the strife, it was pleasant to see the exultation expressed in the faces of the victors, whose joy was manifestly increased by the circumstance that the victory was won in the presence of white men, whom they supposed to be highly distinguished and honored in their nation; a conclusion very natural for them to draw, as they knew the business on which their guests were journeying to Detroit (Burnet 1847:68-70).

The next account of what might have been a football game among the Lenape was written at Fairfield, Thames River, Ontario, on September 5, 1811. It reads:

Some Indians of the Upper Monsey towns camped out near town where they disturbed our rest the entire night with drumming, dancing, and noise. One of them explained they had made this compliment because last spring Br. Schmall had given a warning to several of their young people that ball playing which always is connected with unpleasant noise is not to be done here near us in town (Moravian Archives, folio 8, box 163).

Indian football was also played by the Delawares of Western Oklahoma, a group which split off from the main group of Delawares in the late 1700’s. The following account of the game was given by two of the elders, Willard Thomas and Bessie Snake:

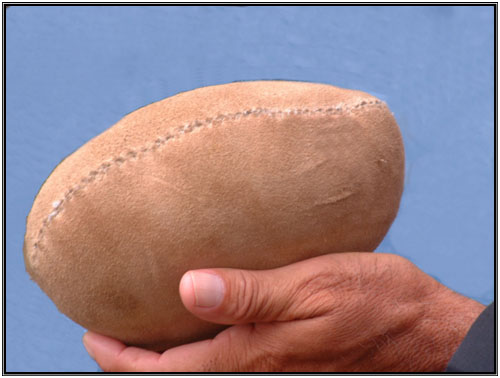

Ball game — they used a soft ball made of deer skin stuffed with hair, about the size of a soft ball. A team had men and women both on it. The rule was the women could throw it, but the men had to kick it. They had a line at the end of the field and the one who got the ball across that line scored a point. It took one score to win. It was really a rough game. They had betting on that game. The field was a little over 100 yards long. They started the game by a man throwing the ball up among a bunch of men and women out in the center. Men could catch the ball, but couldn’t throw it; they had to pass it by kicking it. Men got their shirts torn up and everything else. A bunch of women would grab him and keep him from kicking the ball (Hale 1984:34).

Nora Thompson Dean gave the following account to the Lenape Land Association in Pennsylvania in 1971. The additional comments in square brackets are by the author:

Pahsahëman — Lenape Indian Football

Lenape football is not something that the Delawares have adopted from the whites. The name of the game is Pahsahëman. The ball used in the game is called Pahsahikàn. The Ball is made of deerskin, and is oblong in shape, and is stuffed with deer hair. It is about 9 inches in diameter.

The Playing Field is of no special size. The one near here [Dewey, Oklahoma] is approximately 150 feet long, and, at its narrowest point, 60 feet. This is to say that the goal posts are 150 feet apart. The field is not really bounded by straight lines to

mark the field.

The Teams are two in number. One team being all men, the other all women.3 Thus, the men play against the women. Each team can have any number of players. Young people can also play, but smaller children are usually not allowed to play for fear that they might get hurt.

The Play began when some selected old man or old woman went to the middle of the field and threw the ball into the air (as in basketball). The men and women players would jump up to knock it toward their own goal-post. The men may not carry the ball, nor may they pass it. If a man catches or intercepts the ball, he must stand where he catches it and kick it toward the men’s goal, or toward another man. A man should not tackle or grab a woman who has the ball, but must feign to prevent the woman from passing. He may also knock the ball from her hands. The women players may pass, run with, or even kick the ball. [Mrs. Dean later added that the women would kick at it if it was on the ground, but no high kicks.] They may grab or tackle the men players. [Here too Mrs. Dean added that this would never be a “flying tackle” like in White Man’s football]. The women may throw the ball through the goal-posts, or carry it through.

The Scoring is done by some selected old man or old woman. A pile of twelve sticks (about 2 inches long each) is used to keep score. The sticks are put into two rows (one for men and one for women), one stick each time a goal is made, until

all twelve sticks are used up, then whichever group has the most sticks is the winner. For example, if the women have seven sticks and the men five, then the women are the winners; or, if the women have eleven sticks and the men one, the women are

the winners. If the score is tied, 6 to 6, a play-off takes place until one more goal is made.

The Playing Season begins in the Spring when the weather is nice enough. This can be March or April. The season ends in mid-June, and the older people considered it wrong to play this ball game at other times of the year.4

The Other Rules are few. It is customary, before the first game in the Spring, to have some selected old person make a prayer, much to thank the Creator for having let the people live to play again, and to ask that he might let them live to play in future seasons.

At the end of the last game in mid-June, some old lady takes the ball and makes a prayer, following which she opens the ball letting the deerhair fall to the ground. The hide is given to someone to be kept and made into another ball for the next Spring (if it is in good enough condition).5

Although this is not a rule it may be of interest. If the women are losing a game, one of their favorite “tricks” is to give the ball to some tottery old lady who walks through the goal-posts with the ball, often helped by some of the younger women. This is because they know that the men would not try to touch or knock the ball from that old lady’s hands.6

No set number of games is played, just until the people are tired. Usually the games begin in the afternoon.

A bet-string is passed around the camps or among the people. This is a long string on which people who wish to bet tie something such as a head scarf, handkerchief, or even a ribbon. If the team on which the person bets wins, the person can go and get anything off this bet-string that has not been spoken for.

This concludes the account by Mrs. Dean. The Lenape Football Game continues into the present day. As recently as September, 2012 the game was played at the Delaware Powwow at the Fall-Leaf Dance Grounds near Copan, Oklahoma.

Conclusions

According to the accounts written in the first half of the 1600’s, an Indian football game was played by tribes both north and south of the Lenape. One account was possibly about the football game among the Lenape. The Shawnees did not arrive in the Delaware Valley until the latter part of the 1600’s, and the evidence suggests that the Lenape were playing the game long before that time.

Acknowledgments

This article was compiled by Jim “Lenape Jim” Rementer, and was published in the Bulletin #48 (1993) of the Archaeological Society of New Jersey.

First and foremost I would like to say how thankful I am that Mrs. Dean wrote out the rules of the game. This represents just a small part of her work of many years in trying to preserve the knowledge of the ways of her Lenape people.

I would also like to thank Lucy Blalock for her further information on some of the other details of Lenape football. Mrs. Blalock also been worked to preserve Lenape ways, and taught classes in the Lenape Language teaching classes at the tribal headquarters in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

I would also like to express my thanks to Dee Ketchum, Michael Pace, Herbert Kraft, Bruce Pearson, and to David Oestreicher for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Endnotes

1. The Lenape Land Association was founded by Annabelle Bradley, a school teacher. The purpose was to reconstruct a Lenape village as it would have been prior to 1600 for educational purposes. She was unfortunately unable to fulfill her dream mainly due to the cost of acquiring a suitable land base in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

2. It should be noted that someone in Pennsylvania has reprinted Mrs. Dean’s account in a sheet entitled Lenape “Soccer” without giving her credit for having supplied the information.

3. Lucy Blalock, a Lenape elder, added the comment that a woman who is menstruating should not take part in the game.

4. This author discovered (as did Frank Speck), in researching the rules of the game, that the Lenape people are rather evenly divided on the time of year to stop playing the game. Some Lenape, such as Mrs. Blalock, say that the

game can be played throughout the summer and fall.

5. The Lenape who say the game can be played throughout the year say that the ball is not torn up at the end of the playing season as long as it remains in good condition.

6. Mrs. Blalock told the author that in the Lenape game, if the men were way ahead in their score, the scorekeeper(s) could select some man to play on the women’s team. This was done in order to keep the teams more evenly

balanced. The selected man played by the same rules as the women; that is, he could run with the ball or pass it.

References

Arber, Edward. 1910. Travel and Works of Captain John Smith. In “Relation of Virginia”, A.G. Bradley edition, 2 vols., Edinburgh, John Grant.

Burnet, Jacob. 1847. Notes on the Early Settlement of the North-western Territory, The Mid-American Frontier. D. Appleton, New York.

Culin, Stewart. 1907. Games of the North American Indians. Bureau of American Ethnology, no. 24, 1902-1903, Washington, D.C.

Dean, Nora Thompson. 1971. Pahsahëman – Indian Football. In Newsletter of The Lenape Land Association, New Hope, Pennsylvania, April issue.

Denton, Daniel. 1670. A Brief Description of New York: Formerly Called New Netherlands. Columbia University Press for the Facsimile Press Society, 1937.

Flannery, Regina. 1939. An Analysis of Coastal Algonquian Culture. The Catholic University of America Press, Washington, D.C.

Goddard, Ives. 1978. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 15 — Northeast. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Hale, Duane K. 1984. Turtle Tales: Oral Traditions of the Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma. Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma Press, Anadarko, Oklahoma.

Harrington, Mark Raymond. 1913. “A Preliminary Sketch of Lenape Culture.” American Anthropologist (new series) 15:208-235.

Howard, James H. 1981. Shawnee! The Ceremonialism of a Native American Tribe and Its Cultural Background. Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio.

Moravian Archives, Bethlehem, PA, folio 8, box 163.

Speck, Frank G. 1937. Oklahoma Delaware Ceremonies, Feasts and Dances. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, vol, 7, Philadelphia.

Strachey, William. 1849. The History of Travelle into Virginia Britannia. The Hakluyt Society, London.

Swanton, J.R. 1928. Aboriginal Culture of the Southeast. Bureau of American Ethnology, no. 42, 1924-1925, Washington, D.C.

Weslager, C.A. 1978. The Delaware Indian Westward Migration. The Middle Atlantic Press, Wallingford, PA.

Williams, Roger. 1643. Key into the Language of America. London.

D5 Creation

D5 Creation