Pahsahëman — The Lenape Indian Football Game

Based on a paper by Jim Rementer, published in Bulletin #48 of the Archaeological Society of New Jersey (1993) and updated with additional information and photographs for the Tribal website.

It is a beautiful morning in late Spring. The year is 1600. In a large open field near one of their main villages (in an area the white people would later name Philadelphia) the people are playing a game. Laughter can be heard from the participants and spectators alike. The people relish these carefree moments playing their game which they call Pahsahëman. Little did they know as they played the game that four hundred years later their descendants would be playing the same game, however, their location had change because they were now in a far-off land called Oklahoma.

- Scene of a Lenape Football Game as might have been played on a Beach in what is now New Jersey. Drawing by Delaware artist Clayton Chambers

Introduction

The games played by the Lenape or Delaware Indians have not been well documented. When they have been mentioned in the literature, many details of the games are sadly lacking.

The Lenape Indians have long played a version of football which differs markedly from the football game known to non-Indians. In the Lenape football game, men are pitted against the women in a very rough-and-tumble game.

We are giving the rules of the game which were written out by the late Nora Thompson Dean (Touching Leaves Woman) for the Lenape Land Association in Pennsylvania.1 Since the organization no longer exists, this information which was printed in their newsletter in April, 1971, would otherwise be lost.2 We begin with a brief history of the game.

History of the Game

Various forms of football were played along the northeast coast of America. Flannery (1939:187) regards football as one of “forty-three traits [which] may be due to independent invention in the coastal Algonquian region, since they are not characteristic of the Iroquoian, Southeastern, or Northern Algonquian areas.” Football games were also recorded for the Micmac, Abnaki, Malecite, Massachusetts, and Narragansett (Flannery 1939:187). Swanton (1928:707) also says it is “apparently a coastal Algonquian game, not found in the Southeast except among the Creeks.”

Some forms of football were played men-against-men as among the Massachuset in 1634, reported by William Wood (Culin 1901:698). In a number of cases the text does not indicate whether the teams were composed of men only, or men-versus women. A good example is the following brief account by Roger Williams who wrote about “pasuckquakohowauog,” which he translates as “they meet to foot-ball.” He says:

They have great meetings of foot-balle playing, only in summer, town against town, upon some broad sandy shore, free from stone, or upon some soft heathie plot, because of their naked feet, at which they have great stakings, but seldom quarrel (Williams 1643:146).

Some writers (Speck 1931:76 and Goddard 1978:231) claim the Lenape learned this game from the Shawnee. In fact, we have no very early descriptive accounts of the game among the Lenape. Neither do we have any early accounts for the game among the Shawnee, so far as this writer knows.

We know from historical accounts that at least some of the Shawnee arrived in the homeland of the Lenape about the year 1692, and settled near the Delaware River in eastern Pennsylvania (Howard 1981:7).

Thirty-six years earlier, in 1656, Daniel Denton wrote, “Their Recreations are chiefly Foot-ball and Cards, at which they will play away all they have, excepting a Flap to cover their nakedness” (Denton 1670:7).

Unfortunately Denton uses the term “Indians” to describe any and all tribes he met in the area, so we cannot be certain whether the game was used by groups of the Munsee Delawares, or Montauk farther east on Long Island, or both. However, this does tell us that a form of a football game was being played by Delawares or closely related tribes living just north and east of the main body of Lenape at least as early as 1656.

At the Jamestown settlement in Virginia, we find an account of the football game by Henry Spelman. He was captured and raised by the Indians for two years (1609-1610) and later served as interpreter for the colony. In his account of the game, he says:

They [the Virginia Indians] use beside football play, which wemen and young boyes doe much play at. The men never. They make ther Gooles as ours only they never fight nor pull one another doune (Arber 1910:CXIV). [His comment, “The men never,” frequently applies to the game today as most of the male players are older boys and young men.]

Another account written about 1610 from the same area reads:

Likewise they have the exercise of football, in which they only forcibly encounter with the foot to carry the ball the one from the other, and spurned it to the goal with a kind of dexterity and swift footmanship, which is the honour of it; but they never strike up one another’s heels, as we do, not accompting that praiseworthy to purchase a goal by such as advantage (Strachey 1849:77).

After the Denton account, the next account of a Delaware football game was in the 1790s.

The party, however, were received very kindly by the venerable old Delaware chief Bu-kon-ge-he-las, whose name has been given to a fine mill-stream in Logan county. He was one of the chiefs who negotiated the treaty at the mouth of the Big Miami, with General George R. Clark, in 1786, in which his name is written Bo-hon-ghe-lass.

In the course of the afternoon he got up a game of football, for the amusement of his guests, in the true aboriginal style. He selected two young men to get a purse of trinkets made up, to be the reward of the successful party. That matter was soon accomplished, and the whole village, male and female, in their best attire, were on the lawn; which was a beautiful plain of four or five acres, in the center of the village, thickly set in blue grass. At each of the opposite extremes of this

lawn, two stakes were set up, about six feet apart.

The men played against the women; and to countervail the superiority of their strength, it was a rule of the game, that they were not to touch the ball with their hands on the penalty of forfeiting the purse; while the females had the privilege of using their hands as well as their feet; they were allowed to pick up the ball and run and throw it as far as their strength and activity would permit. When a squaw succeeded in getting the ball, the men were allowed to seize —whirl her round, and if necessary, throw her on the grass for the purpose of disengaging the ball—taking care not to touch it except with their feet.

The contending parties arranged themselves in the center of the lawn—the men on one side and the women on the other—each party facing the goal of their opponents. The side which succeeded in driving the ball through the stakes, at the goal of their adversaries, were proclaimed victors, and received the purse, to be divided among them.

All things being ready, the old chief came on the lawn, and saying something in the Indian language not understood by his guests, threw up the ball between the lines of the combatants and retired; when the contest began. The parties were pretty fairly matched as to numbers, having about a hundred on a side, and for a long time the

game appeared to be doubtful. The young squaws were the most active of their party, and most frequently caught the ball; when it was amusing to see the struggle between them and the young men, which generally terminated in the prostration of the squaw upon the grass, before the ball could be forced from her hand.

The contest continued about an hour, with great animation and various prospects of success; but was finally decided in favor of the fair sex, by the herculean strength of a mammoth squaw, who got the ball and held it, in spite of the efforts of the men to shake it from the grasp of her uplifted hand, till she approached the goal, near enough to throw it through the stakes (Burnet 1847:68-70).

When the contending parties had retired from the strife, it was pleasant to see the exultation expressed in the faces of the victors, whose joy was manifestly increased by the circumstance that the victory was won in the presence of white men, whom they supposed to be highly distinguished and honored in their nation; a conclusion very natural for them to draw, as they knew the business on which their guests were journeying to Detroit (Burnet 1847:68-70).

The next account of what might have been a football game among the Lenape was written at Fairfield, Thames River, Ontario, on September 5, 1811. It reads:

Some Indians of the Upper Monsey towns camped out near town where they disturbed our rest the entire night with drumming, dancing, and noise. One of them explained they had made this compliment because last spring Br. Schmall had given a warning to several of their young people that ball playing which always is connected with unpleasant noise is not to be done here near us in town (Moravian Archives, folio 8, box 163).

Indian football was also played by the Delawares of Western Oklahoma, a group which split off from the main group of Delawares in the late 1700’s. The following account of the game was given by two of the elders, Willard Thomas and Bessie Snake:

Ball game — they used a soft ball made of deer skin stuffed with hair, about the size of a soft ball. A team had men and women both on it. The rule was the women could throw it, but the men had to kick it. They had a line at the end of the field and the one who got the ball across that line scored a point. It took one score to win. It was really a rough game. They had betting on that game. The field was a little over 100 yards long. They started the game by a man throwing the ball up among a bunch of men and women out in the center. Men could catch the ball, but couldn’t throw it; they had to pass it by kicking it. Men got their shirts torn up and everything else. A bunch of women would grab him and keep him from kicking the ball (Hale 1984:34).

Nora Thompson Dean gave the following account to the Lenape Land Association in Pennsylvania in 1971. The additional comments in square brackets are by the author:

Pahsahëman — Lenape Indian Football

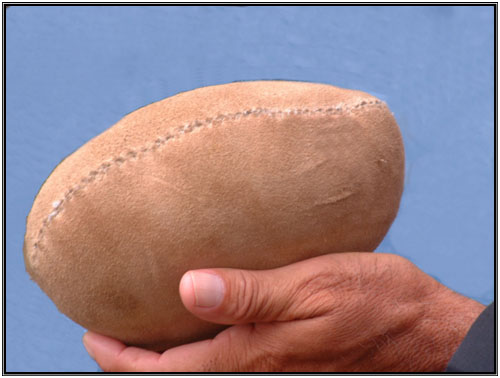

Lenape football is not something that the Delawares have adopted from the whites. The name of the game is Pahsahëman. The ball used in the game is called Pahsahikàn. The Ball is made of deerskin, and is oblong in shape, and is stuffed with deer hair. It is about 9 inches in diameter.

The Playing Field is of no special size. The one near here [Dewey, Oklahoma] is approximately 150 feet long, and, at its narrowest point, 60 feet. This is to say that the goal posts are 150 feet apart. The field is not really bounded by straight lines to

mark the field.

The Teams are two in number. One team being all men, the other all women.3 Thus, the men play against the women. Each team can have any number of players. Young people can also play, but smaller children are usually not allowed to play for fear that they might get hurt.

The Play began when some selected old man or old woman went to the middle of the field and threw the ball into the air (as in basketball). The men and women players would jump up to knock it toward their own goal-post. The men may not carry the ball, nor may they pass it. If a man catches or intercepts the ball, he must stand where he catches it and kick it toward the men’s goal, or toward another man. A man should not tackle or grab a woman who has the ball, but must feign to prevent the woman from passing. He may also knock the ball from her hands. The women players may pass, run with, or even kick the ball. [Mrs. Dean later added that the women would kick at it if it was on the ground, but no high kicks.] They may grab or tackle the men players. [Here too Mrs. Dean added that this would never be a “flying tackle” like in White Man’s football]. The women may throw the ball through the goal-posts, or carry it through.

The Scoring is done by some selected old man or old woman. A pile of twelve sticks (about 2 inches long each) is used to keep score. The sticks are put into two rows (one for men and one for women), one stick each time a goal is made, until

all twelve sticks are used up, then whichever group has the most sticks is the winner. For example, if the women have seven sticks and the men five, then the women are the winners; or, if the women have eleven sticks and the men one, the women are

the winners. If the score is tied, 6 to 6, a play-off takes place until one more goal is made.

The Playing Season begins in the Spring when the weather is nice enough. This can be March or April. The season ends in mid-June, and the older people considered it wrong to play this ball game at other times of the year.4

The Other Rules are few. It is customary, before the first game in the Spring, to have some selected old person make a prayer, much to thank the Creator for having let the people live to play again, and to ask that he might let them live to play in future seasons.

At the end of the last game in mid-June, some old lady takes the ball and makes a prayer, following which she opens the ball letting the deerhair fall to the ground. The hide is given to someone to be kept and made into another ball for the next Spring (if it is in good enough condition).5

Although this is not a rule it may be of interest. If the women are losing a game, one of their favorite “tricks” is to give the ball to some tottery old lady who walks through the goal-posts with the ball, often helped by some of the younger women. This is because they know that the men would not try to touch or knock the ball from that old lady’s hands.6

No set number of games is played, just until the people are tired. Usually the games begin in the afternoon.

A bet-string is passed around the camps or among the people. This is a long string on which people who wish to bet tie something such as a head scarf, handkerchief, or even a ribbon. If the team on which the person bets wins, the person can go and get anything off this bet-string that has not been spoken for.

This concludes the account by Mrs. Dean. The Lenape Football Game continues into the present day. As recently as September, 2012 the game was played at the Delaware Powwow at the Fall-Leaf Dance Grounds near Copan, Oklahoma.

Conclusions

According to the accounts written in the first half of the 1600’s, an Indian football game was played by tribes both north and south of the Lenape. One account was possibly about the football game among the Lenape. The Shawnees did not arrive in the Delaware Valley until the latter part of the 1600’s, and the evidence suggests that the Lenape were playing the game long before that time.

Acknowledgments

This article was compiled by Jim “Lenape Jim” Rementer, and was published in the Bulletin #48 (1993) of the Archaeological Society of New Jersey.

First and foremost I would like to say how thankful I am that Mrs. Dean wrote out the rules of the game. This represents just a small part of her work of many years in trying to preserve the knowledge of the ways of her Lenape people.

I would also like to thank Lucy Blalock for her further information on some of the other details of Lenape football. Mrs. Blalock also been worked to preserve Lenape ways, and taught classes in the Lenape Language teaching classes at the tribal headquarters in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

I would also like to express my thanks to Dee Ketchum, Michael Pace, Herbert Kraft, Bruce Pearson, and to David Oestreicher for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Endnotes

1. The Lenape Land Association was founded by Annabelle Bradley, a school teacher. The purpose was to reconstruct a Lenape village as it would have been prior to 1600 for educational purposes. She was unfortunately unable to fulfill her dream mainly due to the cost of acquiring a suitable land base in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

2. It should be noted that someone in Pennsylvania has reprinted Mrs. Dean’s account in a sheet entitled Lenape “Soccer” without giving her credit for having supplied the information.

3. Lucy Blalock, a Lenape elder, added the comment that a woman who is menstruating should not take part in the game.

4. This author discovered (as did Frank Speck), in researching the rules of the game, that the Lenape people are rather evenly divided on the time of year to stop playing the game. Some Lenape, such as Mrs. Blalock, say that the

game can be played throughout the summer and fall.

5. The Lenape who say the game can be played throughout the year say that the ball is not torn up at the end of the playing season as long as it remains in good condition.

6. Mrs. Blalock told the author that in the Lenape game, if the men were way ahead in their score, the scorekeeper(s) could select some man to play on the women’s team. This was done in order to keep the teams more evenly

balanced. The selected man played by the same rules as the women; that is, he could run with the ball or pass it.

References

Arber, Edward. 1910. Travel and Works of Captain John Smith. In “Relation of Virginia”, A.G. Bradley edition, 2 vols., Edinburgh, John Grant.

Burnet, Jacob. 1847. Notes on the Early Settlement of the North-western Territory, The Mid-American Frontier. D. Appleton, New York.

Culin, Stewart. 1907. Games of the North American Indians. Bureau of American Ethnology, no. 24, 1902-1903, Washington, D.C.

Dean, Nora Thompson. 1971. Pahsahëman – Indian Football. In Newsletter of The Lenape Land Association, New Hope, Pennsylvania, April issue.

Denton, Daniel. 1670. A Brief Description of New York: Formerly Called New Netherlands. Columbia University Press for the Facsimile Press Society, 1937.

Flannery, Regina. 1939. An Analysis of Coastal Algonquian Culture. The Catholic University of America Press, Washington, D.C.

Goddard, Ives. 1978. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 15 — Northeast. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Hale, Duane K. 1984. Turtle Tales: Oral Traditions of the Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma. Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma Press, Anadarko, Oklahoma.

Harrington, Mark Raymond. 1913. “A Preliminary Sketch of Lenape Culture.” American Anthropologist (new series) 15:208-235.

Howard, James H. 1981. Shawnee! The Ceremonialism of a Native American Tribe and Its Cultural Background. Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio.

Moravian Archives, Bethlehem, PA, folio 8, box 163.

Speck, Frank G. 1937. Oklahoma Delaware Ceremonies, Feasts and Dances. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, vol, 7, Philadelphia.

Strachey, William. 1849. The History of Travelle into Virginia Britannia. The Hakluyt Society, London.

Swanton, J.R. 1928. Aboriginal Culture of the Southeast. Bureau of American Ethnology, no. 42, 1924-1925, Washington, D.C.

Weslager, C.A. 1978. The Delaware Indian Westward Migration. The Middle Atlantic Press, Wallingford, PA.

Williams, Roger. 1643. Key into the Language of America. London.

D5 Creation

D5 Creation